Our small household finally caught Covid a month or so ago. I spent my time, in between coughing fits, getting very excited watching various printmakers demonstrate their skills on You-tube. The penny dropped that making images for collagraphy and monotype printing should help resolve my preoccupations with paper collages and how to publish my iPhone and iPad digital collages made over the past decade.

These techniques do not restrict creative spontaneity, as you are in free fall chasing down the final image, when using your fingers to make marks, adjusting and refining the evolving shapes by erasure or adding elements.

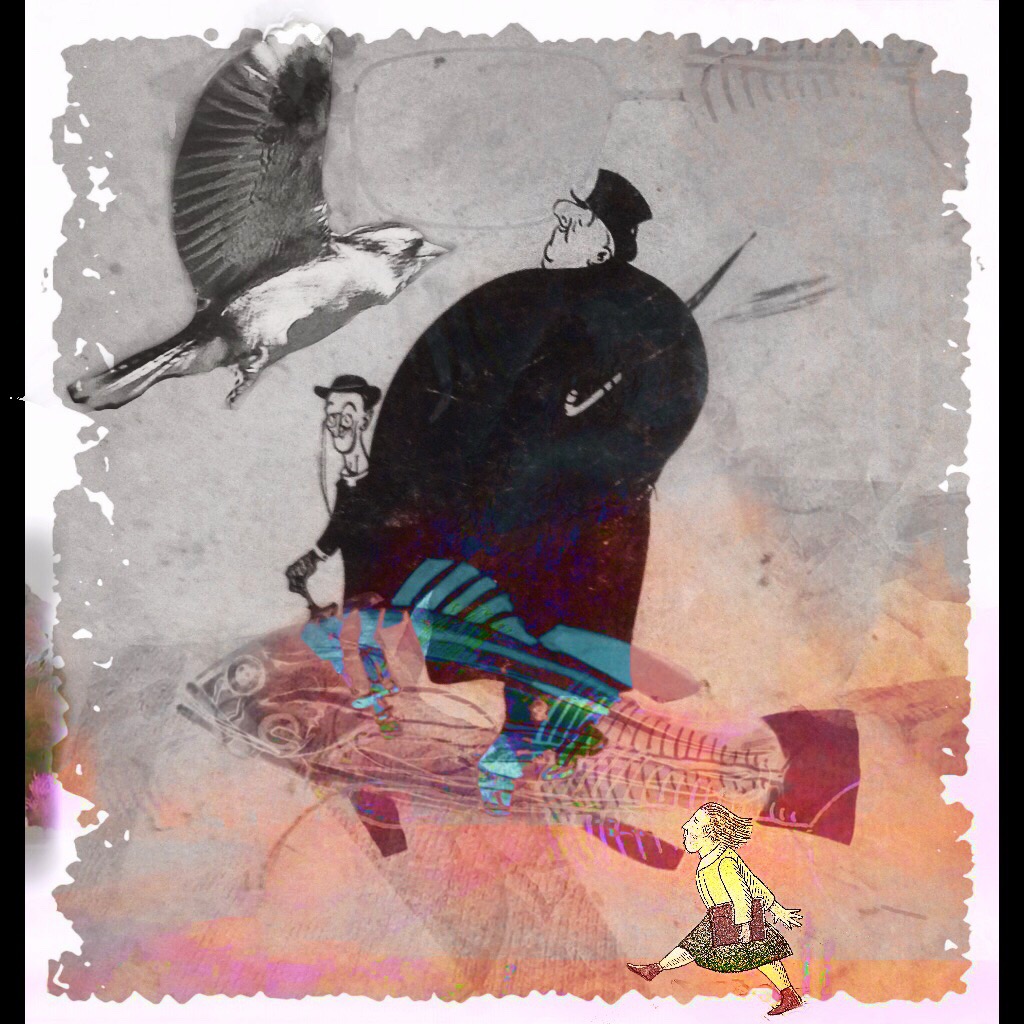

The digital collage below is a doodle made on my iPad using three appropriated images from books of my childhood. A character out of my father’s hard worn H.R. Bateman book and Johnny Head-in-Air from my battered copy of Heinrich Hoffman’s Struwwelpeter.

The Kookaburra and the fish represents part of my childhood in the Warrandyte countryside staying with my grandmother and uncle.

There is also a hint of a contemporary self portrait buried in the background. A mashed digital collage, reworked and refined through various interpretations using my index finger and smart apps on the iPad.

How to publish digital images with ‘added value’, on a low budget, has preoccupied me for some time. David Hockney, whose work already has attached value, explored the potential of the iPad in his exhibited work over the past decade. His curiosity of new technologies, combined with his wonderful sense of colour elevated finger painting on the iPad as an art form. It has always been an issue to turn a digital image, generated in the ethereal world of ones and twos, into a unique object that collectors value – An object with texture, where light plays off its surface and the image exhibits mindfulness and spontaneity behind its creation. It is hard to capture these sensibilities with an inkjet print. You are left with the admiration of an artist’s imagination and technical skill in the reproduction of their paintings, or their patience in compiling a complex digital print or impressed by the scale of the work. Maybe all that is enough. A decade or so ago, some artists sold their digital work on the promise to destroy the data disk and by doing so, give monetary value to a unique work. In some ways NFT blockchain apes this approach and is one response in the age of the internet world awash with digital and art imagery.

Publication and acceptance of digital work by art curators was a vexed area then, and still is.

AI code is evolving sophisticated ‘machine conceived’ imagery, with some people claiming observable ‘sentient’ intent. Is it still art if a person types a concept sentence into a computer program, juxtaposing two objects to make a unique image using the world’s digital online depository? The following AI image is based on two questions: Show me a flying train? Show me an apple orchard? This image was selected from a few trials, mainly because I liked the feather. A quaint touch.

A machine produced image, based on thoughts, showing apparent human sensibilities is unsettling at first glance, particularly if you are a fantasy artist or space nerd. Or is it just another technology available? And it still requires some form of publication! And how is it valued?

Code and technology produce an image with an acceptable aesthetic that appears on screen or in print. It also challenges the economic construct of value attached to art. It is all part of the digital story.

In 2010 I joined a number of artists and programmers in New York to discuss the promise of finger painting on mobile phones and pads using Brushes and other painting apps. Like the curious Hockney, others were attracted to the medium of liquid light at your fingertips. We met to exchange ideas and to see where the medium would lead. An exhibition of digital work was held at the end of the conference and a book published in 2013 showcasing the work of artists who attended the conference. Some of the group went on to explore augmented reality systems, tag projection, web studios or refining their digital skills, while others returned to the wet world of pigment bristle brush and canvas.

Since that time, I have publicly exhibited and sold only a few small digital works as unique prints using a hand crafted wet paper transfer method. The one time I used straight digital prints for an ‘art piece’ fell flat. They were part of an installation at a group show. The digital component of the work used an app that turned a photo of a larger pastel and ink drawing into a 3D image when viewed with 3D glasses. I used my 88-dollar ink jet printer to print my drawing on archival paper displayed within a framed installation including paper sculptured 3D glasses (reworked from a horror movie fire sale).

At the opening I overheard a well-respected photographer, when looking at the work comment, “Is this a joke?” I prompted the patrons to use the 3D glasses provided and left them to it. I do accept the comment if technique is the only arbiter of what gives value to a work. There is more to looking at art than that. Maybe I should have patiently hand drawn the red and green lines rather than use an app? Or deconstructed the layers for reprinting outside the digital realm? The printed drawings still had to be colour adjusted, layered and arranged to compile the 3D scenes. I do remember my 1950s childhood experiments, using red green pencils, studiously drawing Mighty Mouse just like in the 3D comic books.

The overall intent of the work was possibly lost as the larger parent drawing was hung at the other end of the gallery. I note this in defence of the work as I like the work and the joke and to quell the angst of the misunderstood genius behind it. In the real world, it is in the eye of the viewer as to whether they like a work or they don’t and are prepared to put a value on it.

It was a serious joke at the time that is still relevant today, given recent developments in artificial intelligence, and creative imagery publication via the internet. Are we in a modern-day rerun of the William Morris era, where new technology shapes battle lines over defining what is art? Big subject for another time. The intention of this post is a note to myself, to summarise my attempts at different reproduction processes and to assess my evolving practice with the imminent arrival of a small printing press. I’ve got some catching up to do.

UPDATE: Damien Hirst does performance, to add value in the digital realm, by publicly destroying paintings when digitally paired with an NFT Non fungible token. Meanwhile, my instagram account has attracted an entrepreneur wanting to buy a collection of my art works as an NFT, just when I am looking for simpler times…smile.

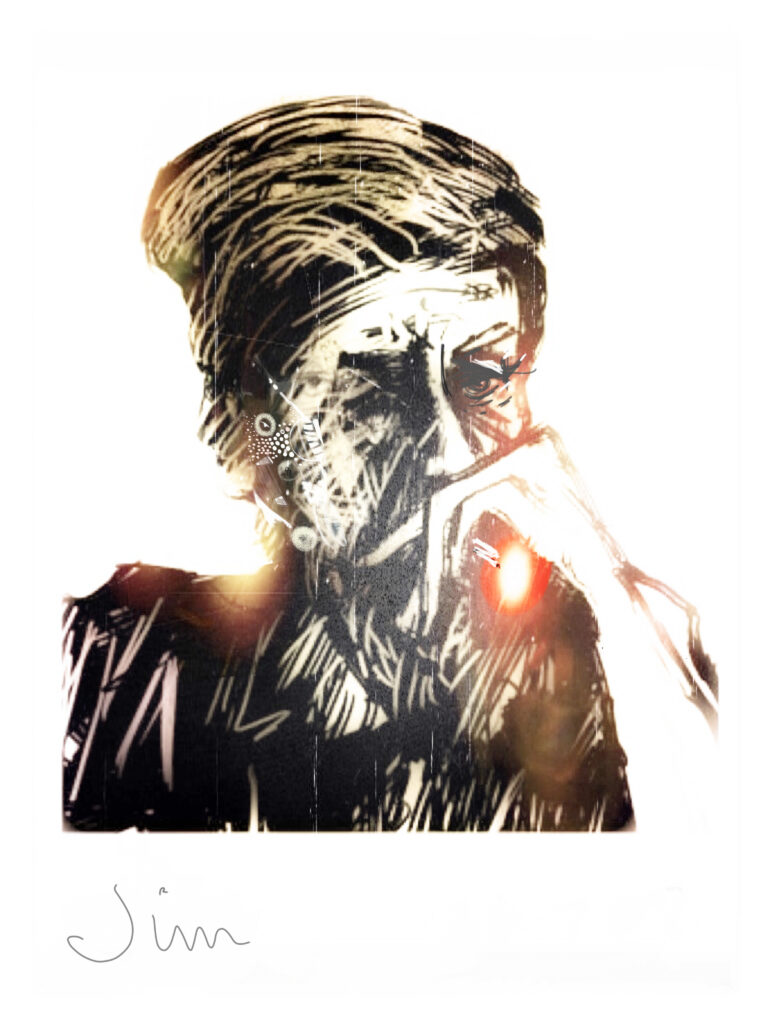

Jim. Wet transfer

Display. Looped display on iPod

iPod finger drawing on display at Nan Giese Gallery, Charles Darwin University. 2011 This show required the full gambit of a radio interview and lecture, with some added drama from Cyclone Carlos

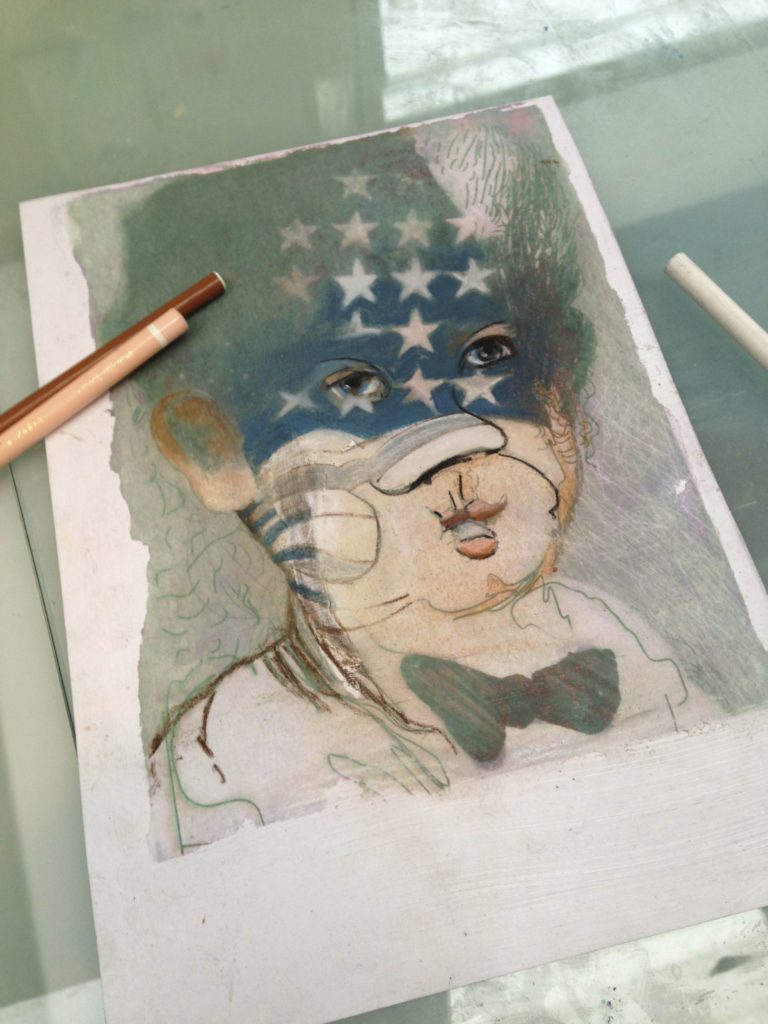

Rubbing-Wet transfer

American Series USA 1- wet transfer.

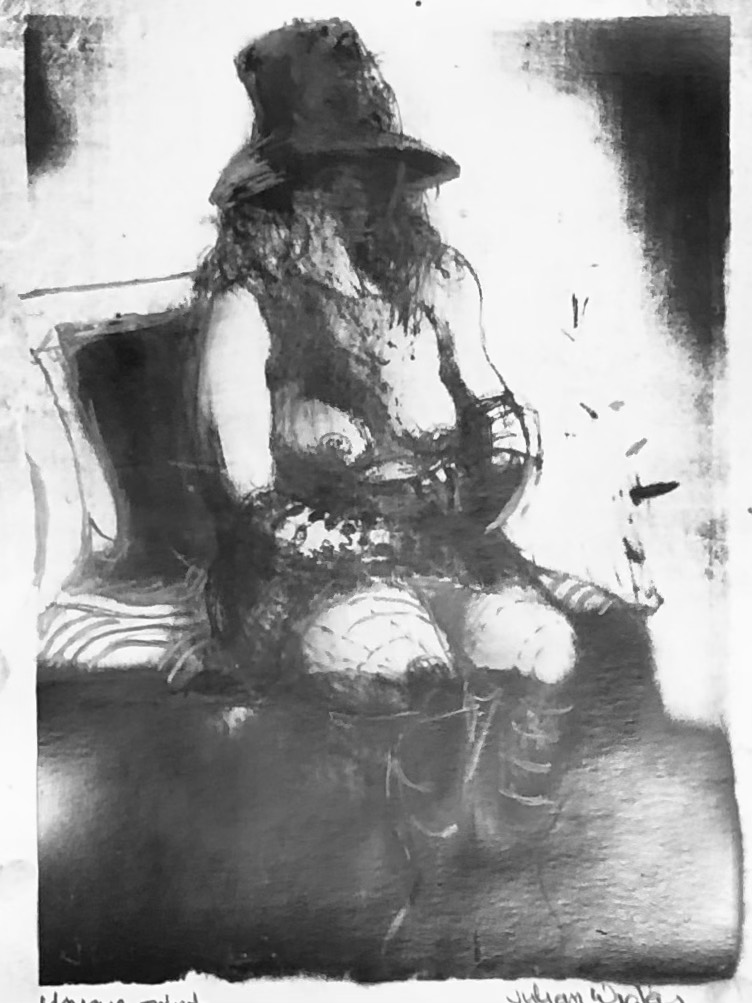

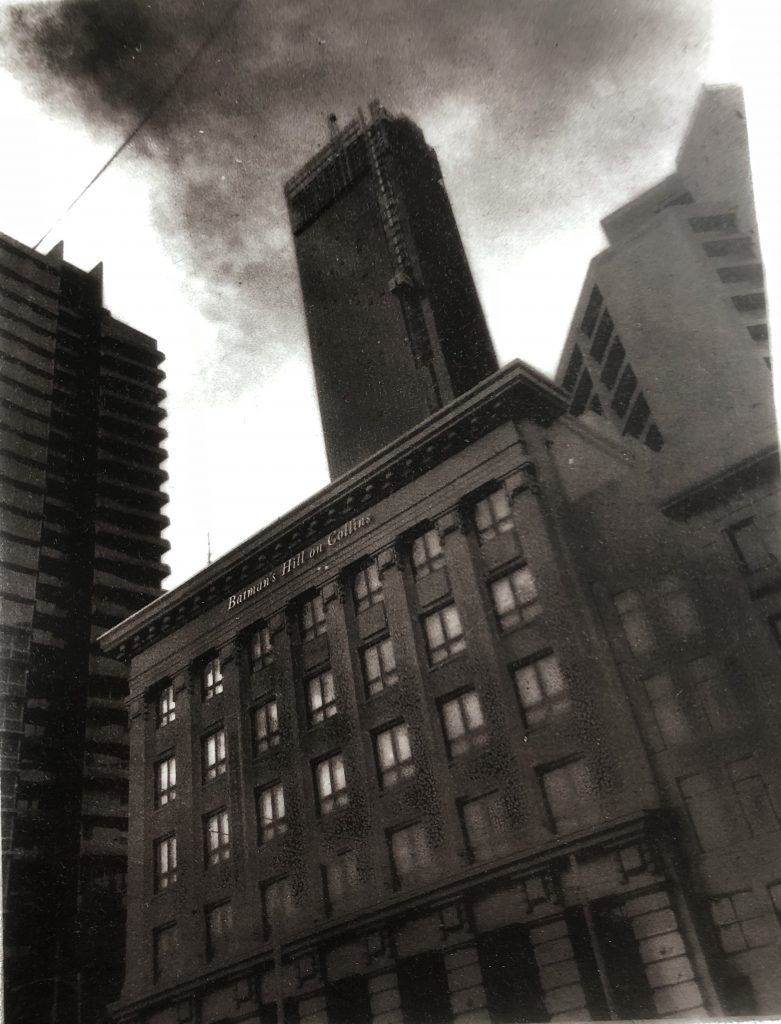

My decade of digital work, buried in various iDevices, may have some life outside their digital existence, through the photopolymer process and other printing techniques such as chine-collé. I’ve experimented printing digital drawings using ink jet printers, film projection, the bromoil process and making unique prints by transferring an ink jet copy of a digital image to a new medium of acrylic ground. This latter process provides a surface texture that softens the print’s appearance and allows some reworking, whereas a Bromoil print retains its photographic origins. Its strength is in the play of light and depth of shadow across the image.

Lady in hat. Bromoil print of digital finger drawing.

City building

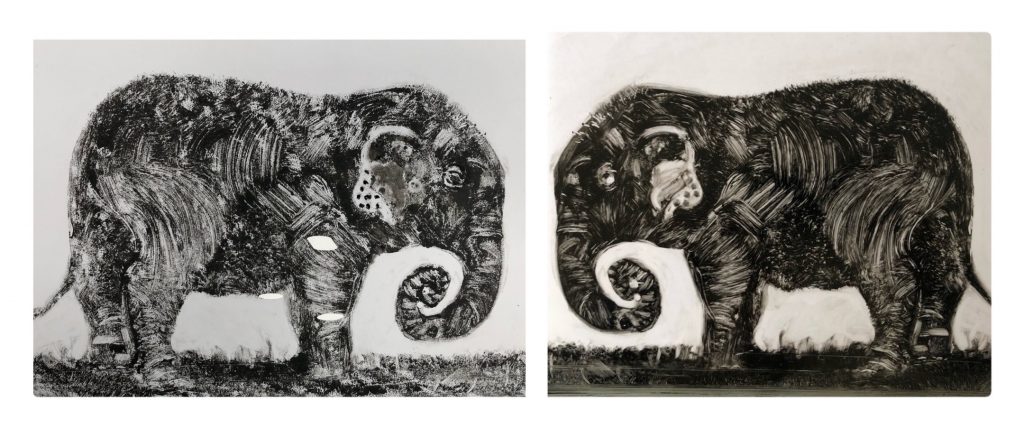

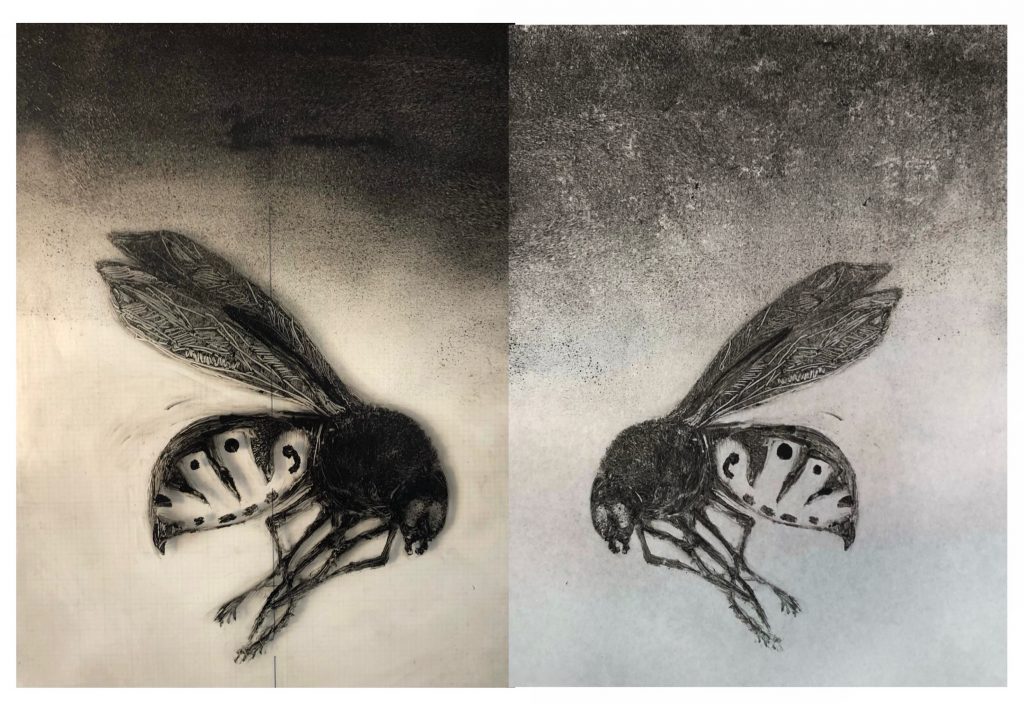

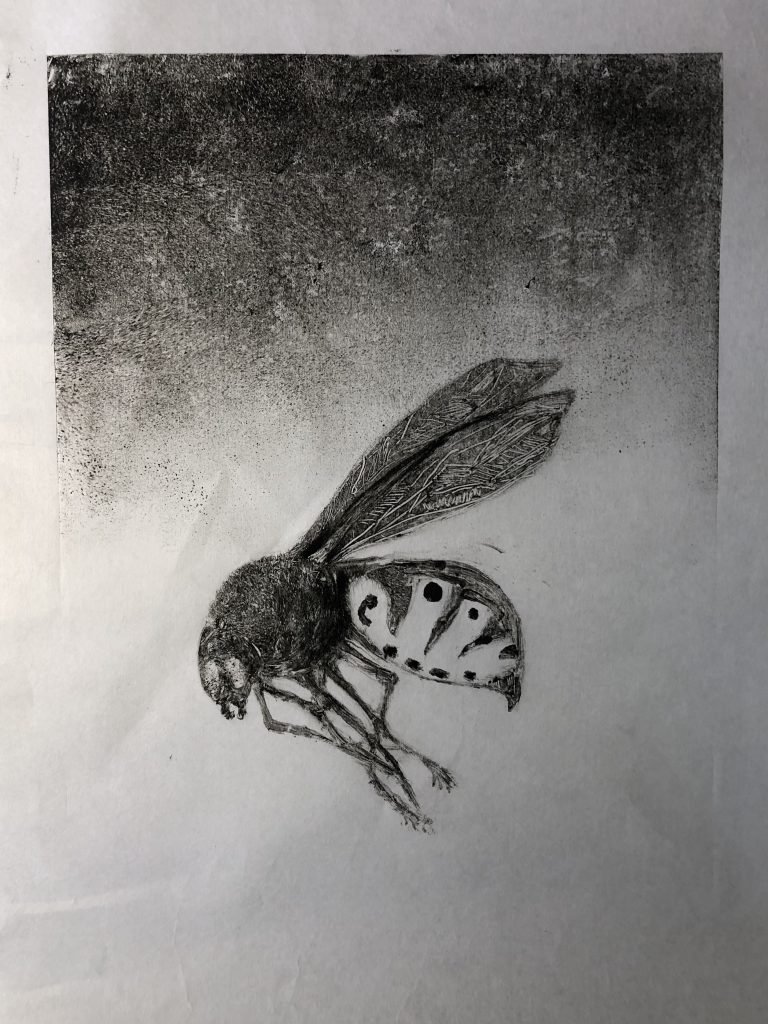

A bottle of Akua Kolor printing ink, that sat on the studio shelf for several years, is now in use, along with my father’s ink dabbers and his assorted etching tools. It’s a strange feeling, entering my last year before hitting eighty, to explore an art form that I have loved looking at, but never pursued with any seriousness. There is no regret in this, as it is never too late.

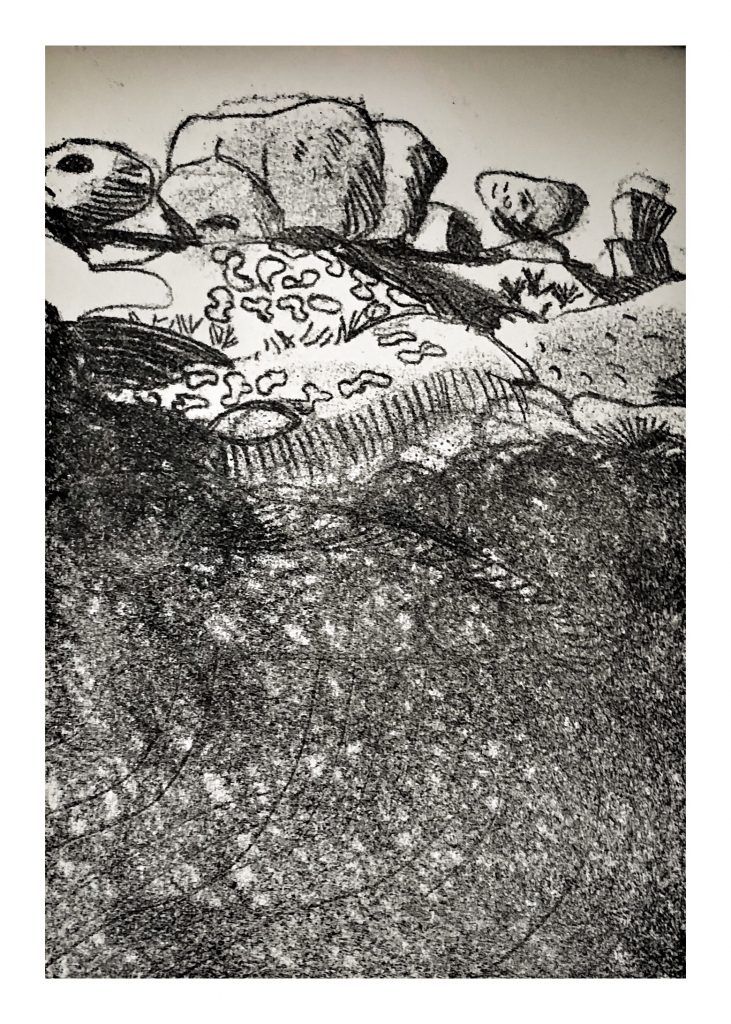

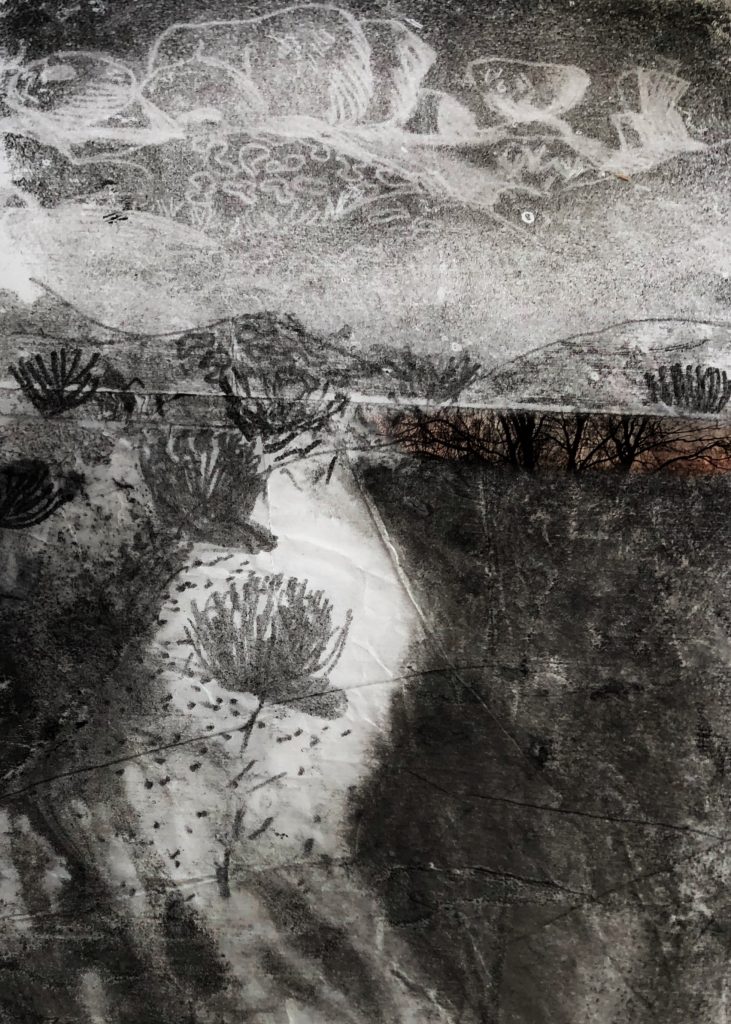

Waiting on an etching press. Meanwhile playing with monotype printing using a baren, homemade tools and working on a new studio layout to seperate work areas.

Gallery: Showing tests using Akura ink (Kolor) rolled on with painters foam roller and pressed using a wooden spoon or baren.

Wiping/ erasure

Plate and image

Ghost print

Combination: painted ink and wiping

Karlu Karlu; Direct drawing to rear of paper

Collage using Ghost prints

This brings me back to the heady art dilemma: Is art made to please the eye and for others to enjoy, or for no less noble reasons, like calling out injustices or challenging the mores and manners of my society? Can art be all of these and is there a balance?

Some of my youthful work ran into trouble. There was the ‘Beggar man 1978’ shown in 1972 at the Ewing Gallery. This mechanical man emitted intermittent sounds of suspect musical worth gave a visiting patron with a medical condition a fright. She objected to its ugliness and it’s inappropriateness in a public space. The gallery stood its ground although I think the sound track was only turned on for special occasions to every bodies relief.

My cafeteria mural at Melbourne I+University (1966) did not survive… it was removed after a month or so and destroyed (as far as I know). Then there are the thousands of copies of Red Heart 2, The mining comic, that ended up in Glebe tip at the direction of the Bishops after pressure from the mining lobby. This is a longer story for some other time.

In recent years I have found enjoyment in softer subject matter and a more contemplative world view taking in colour and light and not always looking for the sting in the tail. But then, as the writer Rabih Alameddine points out, there is art that ‘does not threaten how the dominant culture sees itself’ and then there is the art that shows what is behind the mirror.

“…It’s amazing that the primary artist whose work about AIDS is part of the dominant culture is Keith Haring, not (David) Wojarnowicz. It’s not a criticism of Haring, it’s just that Haring’s work does not threaten how the dominant culture sees itself. I’m fascinated by that…”

[Rabih Alameddine. Interview “Bless the Perverts” -Carlos Motta and Rabih Alameddine in Grand Journal 2022].