‘Jim, an Australian boy’

Julian Wigley

I am interested in writing this story to explore why my father sabotaged his successes on most occasions. Was it because he had ‘scruples,’ as Don McLeod wrote in a letter sometime in the late seventies or early eighties?

“Box 139 Port Headland 6721

15 July

Dear Jim,

In the past you have tended to allow your scruples to rob your opportunity. This might be an occasion by which you could if you had something suitable pick up a few dollars from the yokels who will bend anything to prevent people realising what they have done to the black fellas.

Things are much as usual here sometimes I think we are winning mostly, I know we aint (sic).

But at least we still worry the bastards

Yours Sincerely

D.W McLeod”

Don’s use of the word ‘scruples’ hinted at another Jim, one I suspected was always there, not the two Jims I alternately experienced—the drunk Jim or the sober Jim. I hope this story provides some insights into the man.

For those unaware of Don McLeod, he was a communist and activist who committed his life to the Strelley Mob in the Pilbara. He and Jim were comrades from 1957 until their deaths, coincidentally in 1999.

Notes

©️ Julian Wigley 2024 and all images ©️ Julian Wigley 2024 unless stated otherwise.

WARNING: This document contains names and photographs of deceased persons.

The terminology of the period has been retained to reflect common usage and historical accuracy. For example, terms such as piccaninnies to describe young children and native to refer to Indigenous people were typical of earlier times. I personally heard both terms used in the 1970s. For my historical accuracy, I have used whitefella and blackfella, which encompass all genders, as these terms reflect my lived experience and observed interactions.

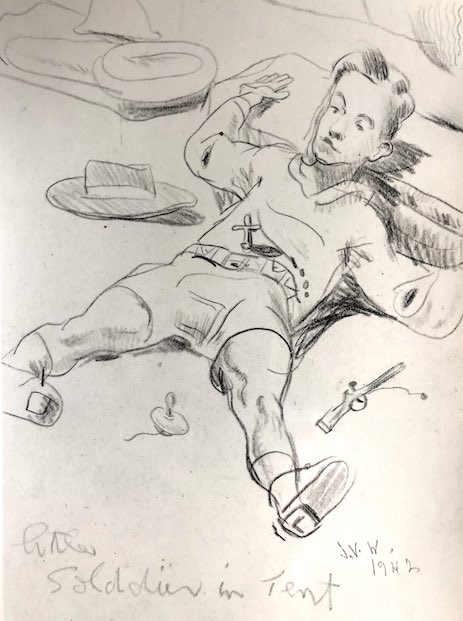

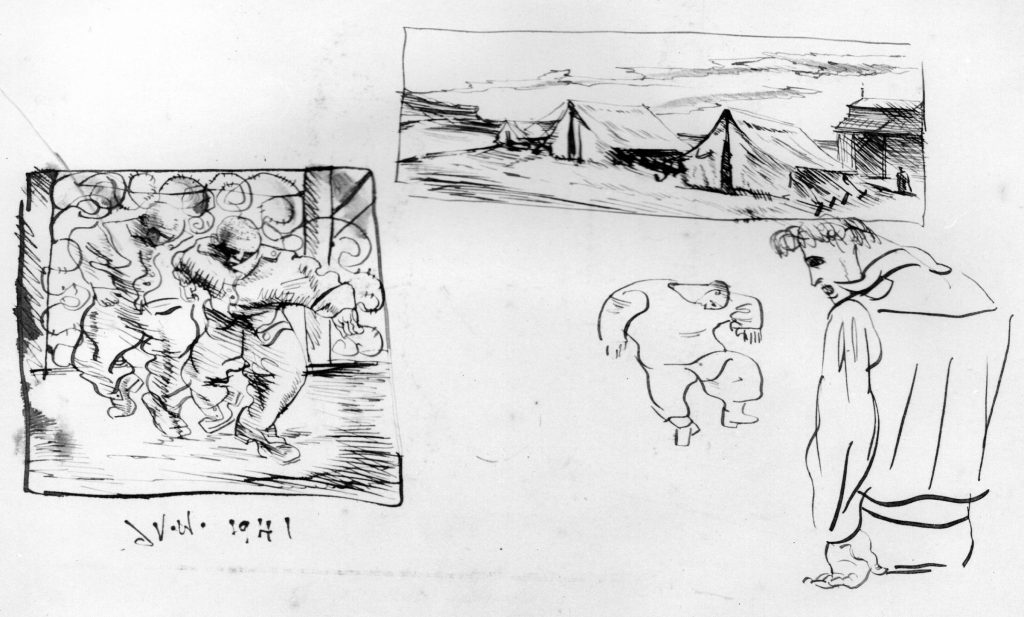

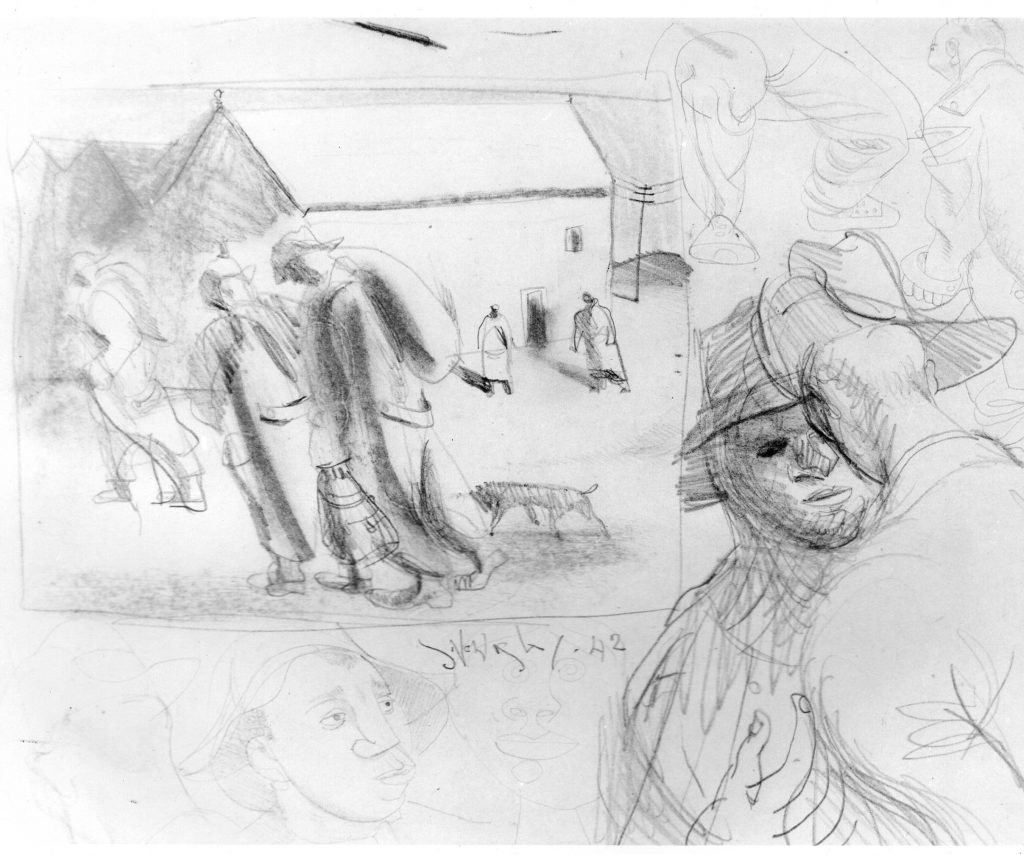

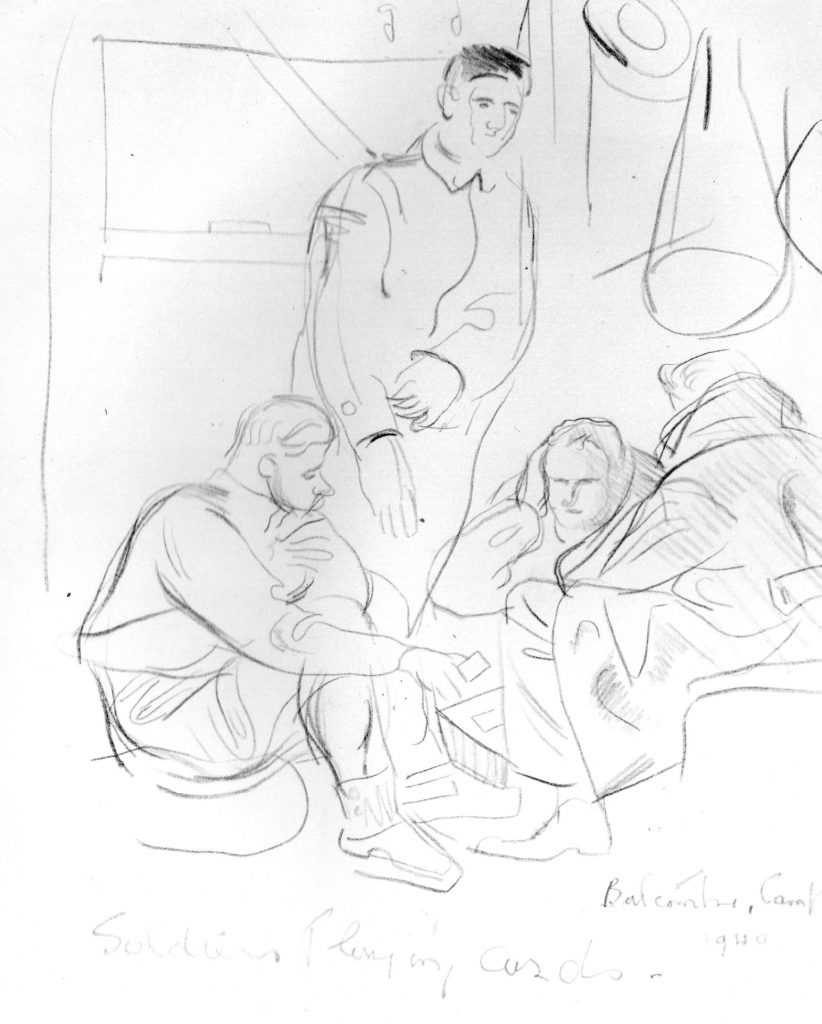

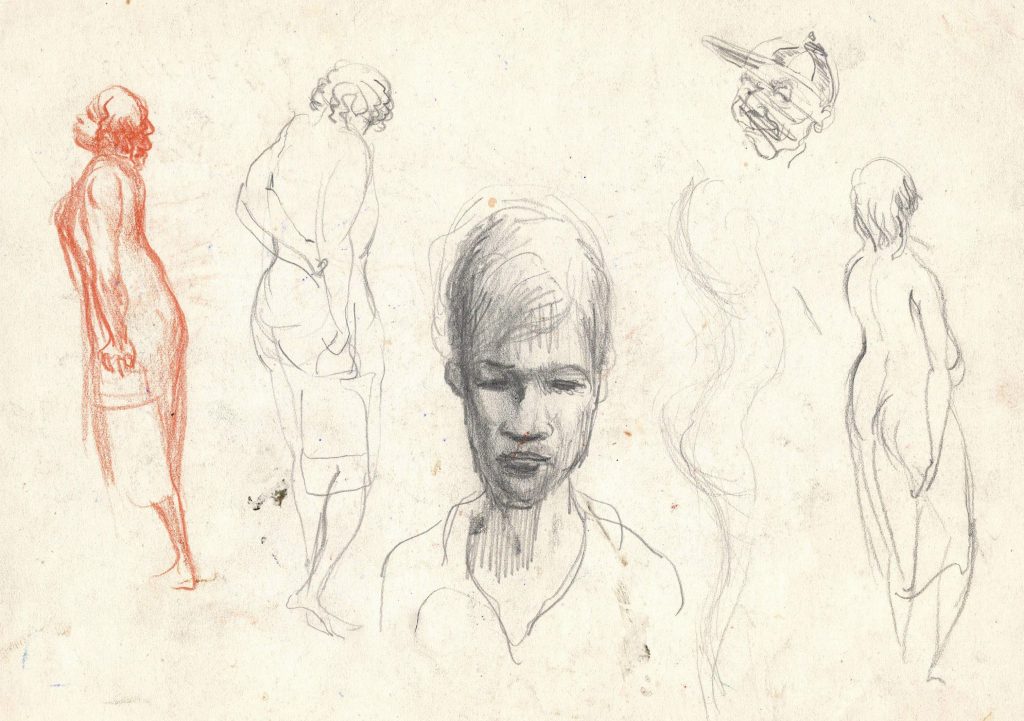

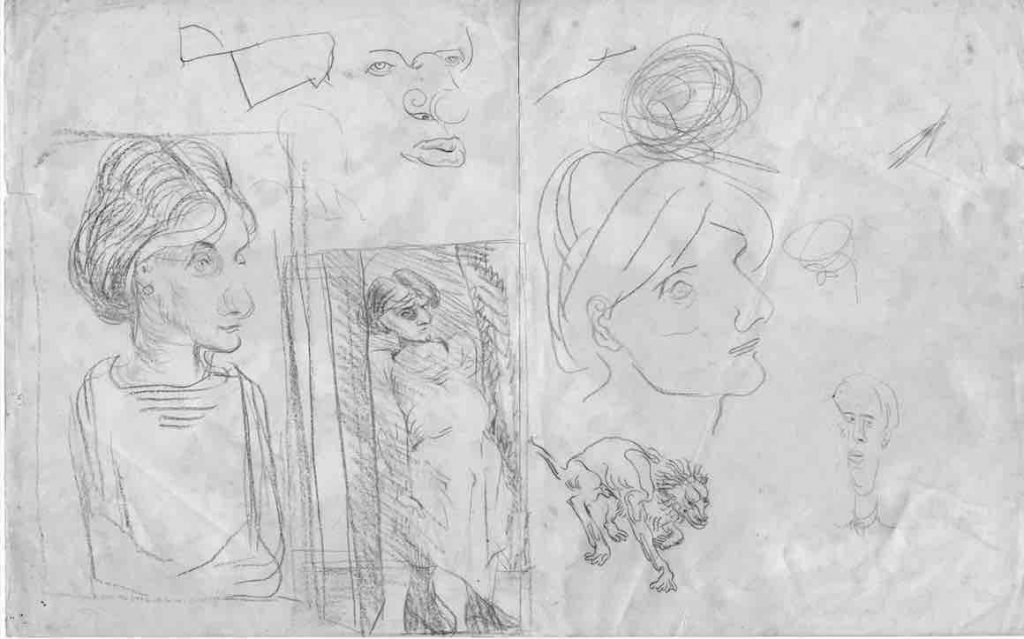

The images used are from Jim’s sketchbooks, papers, and drawing folios. The end notes list other resource material, references, and acknowledgements.

***

Note: this document is live (work in progress).

Request: If you are the owner of Jim’s last painting, ‘Snapshot, Darwin,’ would you please get in contact? I would like a colour photo for publishing purposes.

Preface

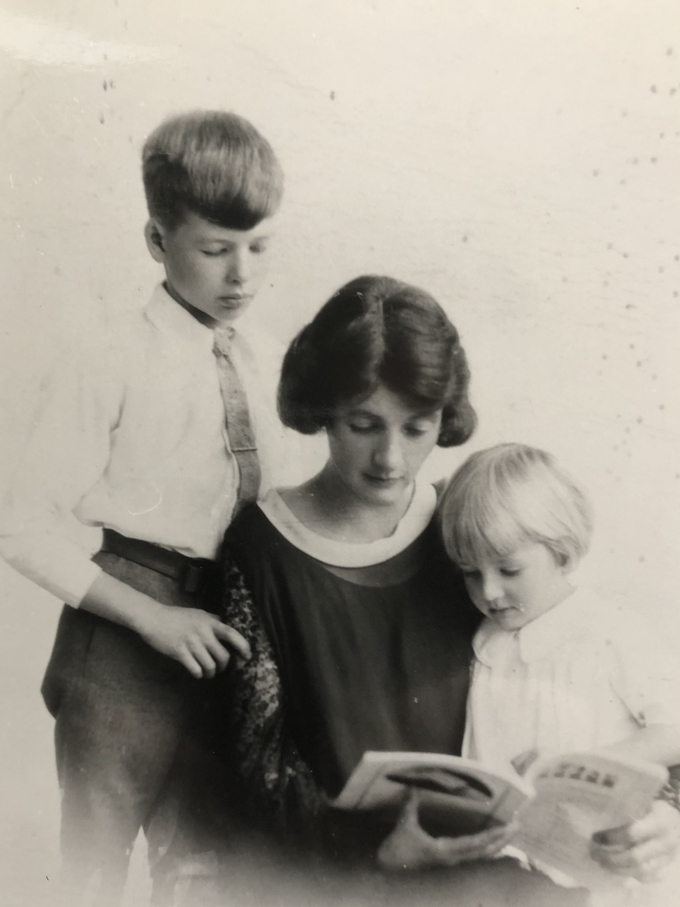

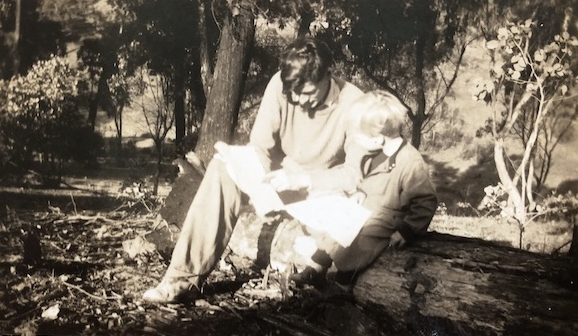

“My father – Jim – lived in a suitcase under my grandmother’s cottage in Warrandyte. When he was real, he lived up the hill with Mum and me, occasionally.”

— From Catch Him By His Name

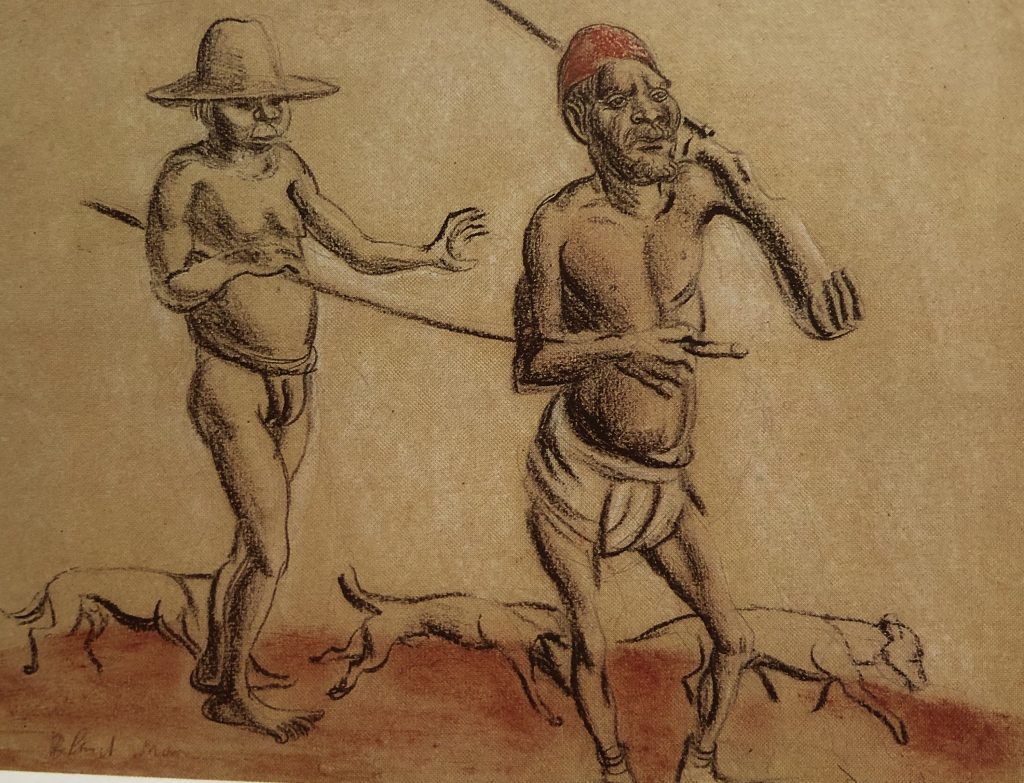

Over the years, I tracked my father’s life as his paintings changed on my grandmother’s wall: a pastel drawing on butcher’s paper, dated 1945, drawn on the banks of the Daly River in the Northern Territory, showing two men accompanied by three dogs, walking in single file, holding a stick between them – ‘Blind Man.’ A large oil painting was added a few years later, painted in the 1950s, of a barmaid leaning on the counter of the Grey Eagle Pub in Whitechapel, London, to be replaced a decade later by a streetscape of Glebe terraces in Sydney, NSW.

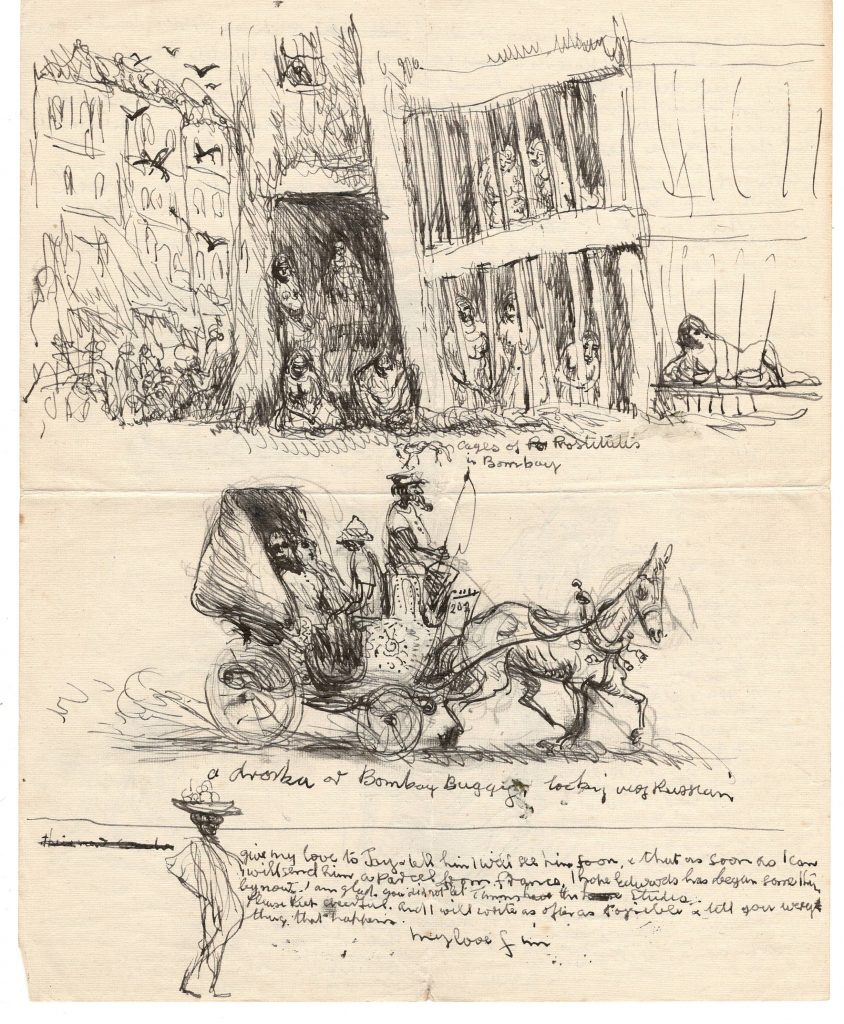

My grandmother provided snippets of my occasional father’s life as I sat beside her bed and she read his letters. I looked at his pictograms of exotic places sketched in the margins. Rusty, my dog, also spent much time at my grandmother’s side. Rusty was half dingo, half kelpie, with half a tail, the missing half lost under the school bus. Each morning and evening, Rusty would chase the school bus, snapping at the front wheels until he could no longer keep up. I say Rusty was my dog, but Jim’s letters to Dove always asked about Rusty, rarely about Mum and me.

As I grew older, I began to find him in the pages of art books—sometimes as a footnote, a brief sentence, or a mention at the tail end of a paragraph about the Social Realists and their art. More recently, others have written about his life and work: Sheridan Palmer and Jane Eckett in — James Vandeluer Wigley (1917–1999), and Inge Kral and Darren Jorgensen — James Wigley and the Strelley Mob: Social Realist Painting in an Aboriginal Community.

At the age of 80, and with my parents long dead, I finally found the courage to listen to my father, Jim, recount his life to Barbara Blackman at the age of 70. I listened for the things left unsaid, hoping to fill the gaps and silent spaces of his life while also searching for answers to my own story, which I am writing. This short story, however, is about Jim—an Australian boy—whose journey stretches from the quiet streets of Adelaide to the Bohemia of Warrandyte, post-war Europe, and the deserts of northern Australia. In writing this story, I have drawn on information from my two memoirs: Red Heart No. 3: Catch Him by His Name and Sticks and Stones: The Early Years.

Part 1

The Making of Jim

The Adelaide art world expected a lot from the 20-year-old Jim, hoping he would uphold the artistic legacy of South Australia and maintain or surpass the traditions of H.M. Bateman and Mortimer Mempes, both known as ‘Adelaide boys.’

“Young James Wigley, of whom great things are expected, has taken up residence in Sydney…Wigley will make his mark and be a credit to the State of his birth. It is the way of these sensitive, shy dreamers…he has been recognised…an art connoisseur was most emphatic that in him was genius of a high order, and that he would become in time and, was in fact now, the local successor of (Will) Dyson in his depiction of the social life of the people. Providing he keeps clear of those ‘artistic ‘uplifters’ who infest the art world of New South Wales. People here need have no qualms as to his future.”

Trove Palette ‘Young S.A. Artist in Sydney Studio’ Thursday 17 Feb. 1938 Also the Mail 23 oct 37. Held at the home of Mr Justice Napier at Crafters, Adelaide. The show was organised by Mrs Napier and Mrs Hans Heysen.

Jim attended the North Adelaide School of Fine Arts, where Millward Grey taught him to draw in the Slade tradition of drawing – ‘drawn line and tone trumps painting,’ said Millward. Occasionally, he allowed the use of coloured washes. To earn a crust, the young Jim faced a future as an illustrator and black-and-white artist working for publications and magazines.

Mum also attended the School at the same time. They exhibited together in a group show displaying their student work:

The work of these artists provides an illustration of the growth of art consciousness in South Australia, and the courage of students who have not followed orthodox rules in their choice of subjects or treatment…

… James Wigley portrays a delightful balance between irony and gentle satire, somewhat in the manner of Daumier, with pencil, chalk, and wash as his media. His “Suburban Ladies” is a small piece of mischievous humour and un-malicious realism …

… Molly Burden has a fine coloured drawing with “Old Man of the Sea” and a pleasant design for a fan in No. 1…

The Adelaide art world didn’t expect much from the young Molly Burden or any other woman attending the School. To the cynical, it was a place for young ladies to gain skills before marriage. Their future work was in commercial art, decorative arts, and illustration. The paucity of information and examples of Mum’s work is sad and frustrating but not surprising: marriage, having a baby, and creating a family home were to be her lot.

Jim and Molly were occasionally mentioned together in the social pages of Adelaide newspapers, attending balls and official celebrations. Jim’s family line stretched back to the colony’s founding fathers, while Molly’s family were well-established chemists on King William Street. In her early years, the spelling of her name varied between “Mollie” and “Molly,” possibly reflecting each grandmother’s preference. She settled on “Molly.” (Molly has her own story, which is told in another volume, but I can’t separate the two for now, even though this is Jim’s story).

Accolades flowed, and sales were good at Jim’s first solo show at a private Adelaide residence in October 1937. Elsewhere, the Fates were at work: Danila Vassilieff decided to move to Melbourne following the ‘paucity of sales’ from his second exhibition at the Macquarie Gallery held in Sydney, and Yosl Bergner arrived in Melbourne after leaving Europe before the German invasion of Poland. He joined his sister, Ruth, who had arrived the previous year. These names will become part of Jim’s story.

With the success of his show in his head, and money in his pocket – the equivalent of half a year’s salary for a factory worker – Jim headed to Sydney to try his luck as an illustrator and cartoonist with Sydney publishers. 1 And to see if it was a place to live and work.

His schoolboy friend, Ron Berndt, lived there, so he wasn’t going into the world of ‘uplifters’ without some friendly support. After trotting around looking for work, he soon decided a breakthrough would not happen after run-ins with the Woman’s Weekly, the Bulletin and other magazines – they always wanted a change to what you submitted. With his money running out and ‘the whiff of war in the air,’ he headed back to Adelaide, stopping briefly in Melbourne, where he met up with other painters and realised he had made a mistake thinking the hectic and exciting Sydney was the place to be.2

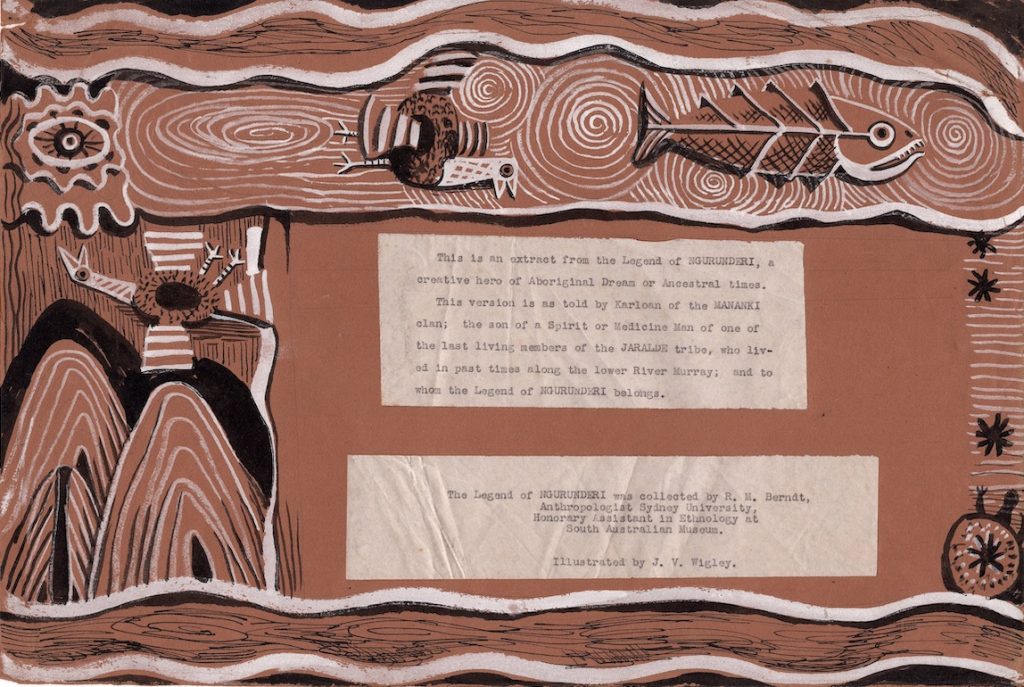

After his return from Sydney, Jim travelled to Murray Bridge in November 1939 with Ron Berndt, who had joined the South Australian Museum as an honorary ethnologist. It was Ron’s first fieldwork expedition to an Aboriginal community and Jim’s first ‘extensive’ visit, drawing alongside blackfellas.

Jim and Ron were students at Pulteney Grammar and became close friends, a friendship that shaped their lives. The school encouraged Jim’s talent for drawing, and when he wasn’t drawing, he found solace and enjoyment in the school gymnasium as a boxer.

Their friendship was founded on their youthful comradeship (they did odd jobs together) and their shared interests. Their relationship shaped their futures before they parted ways.

Warrandyte-‘A little oasis of sanity.’

Churchill delivered his famous “We shall fight on the beaches…we shall never surrender” speech to the House of Commons. Around the same time, Paris fell to German forces, and fascist Italy declared war on both France and the United Kingdom. Japan began making strategic moves in the Pacific, and Jim joined the Army. His anti-fascist sentiments led him to enlist, so he said. He married Mum a few weeks later:

On Tuesday two talented young artists, Molly Burden and Jim Wigley, will be married in St. Columba’s Church, Hawthorn. They will later leave for Melbourne, which is to be their future home. Molly, who has exhibited with the contemporary group is the only daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. Harold Burden and Jim, who is rapidly making a name for himself as a black-and-white artist, is the eldest son of Mrs. Wigley and the late Mr. Harry Wigley.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/55760524?searchTerm=Mollie%2BBurden%20%2Bwigley

Jim and Molly headed east to Melbourne with its promise of bohemia, a place to build a future together and be with like-minded people to face the worries and uncertainties of a world war: Molly with her allowance from the Public Trustees, and Jim, with a promise of fame and fortune as an artist. A promise interrupted by Army Service.1

On their arrival in Melbourne in early 1941, they rented a cottage on Powlett Street, East Melbourne, and met Albert Tucker, Danila Vassilieff, and other painters. Their stay was short-lived, as the rent was too high, and they had to find a cheaper place. Vassilieff suggested Warrandyte, where many artists and writers lived and worked and where there was a progressive school offering employment.2

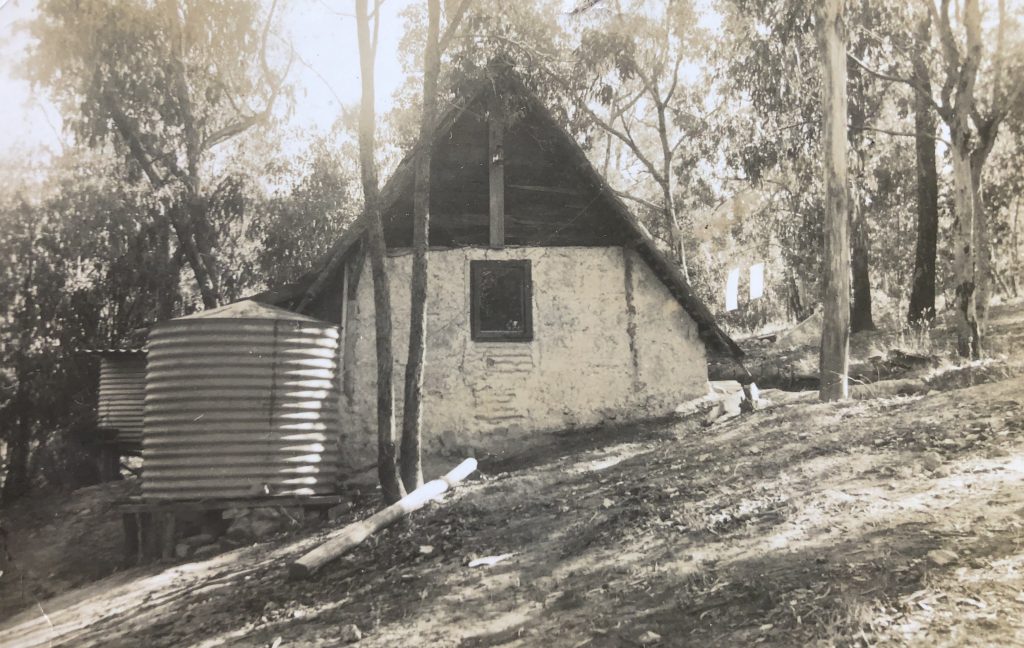

They rented a cottage from Alec and Connie Smith. Connie was a keen supporter of local artists and potters, and Alec was a surveyor and part-time real estate agent. Alec sold 5 acres of bushland to my parents, where Jim was to build a temporary home – a Wattle and Daub bush hut.

Molly and Jim lived in the bush hut while she planned the family home—the Stone House—with the help of their neighbour, Fritz Janeba, an architect trained in the Bauhaus tradition. He was tasked with designing two houses connected by a dirt track on opposite sides of the valley. A roughly hewn log-and-plank bridge crossed the creek running between the two hills. I mention this bridge of logs as it was where trolls waited under its planks and where, when a little older, I would catch tadpoles as they wriggled out from under its shadow.

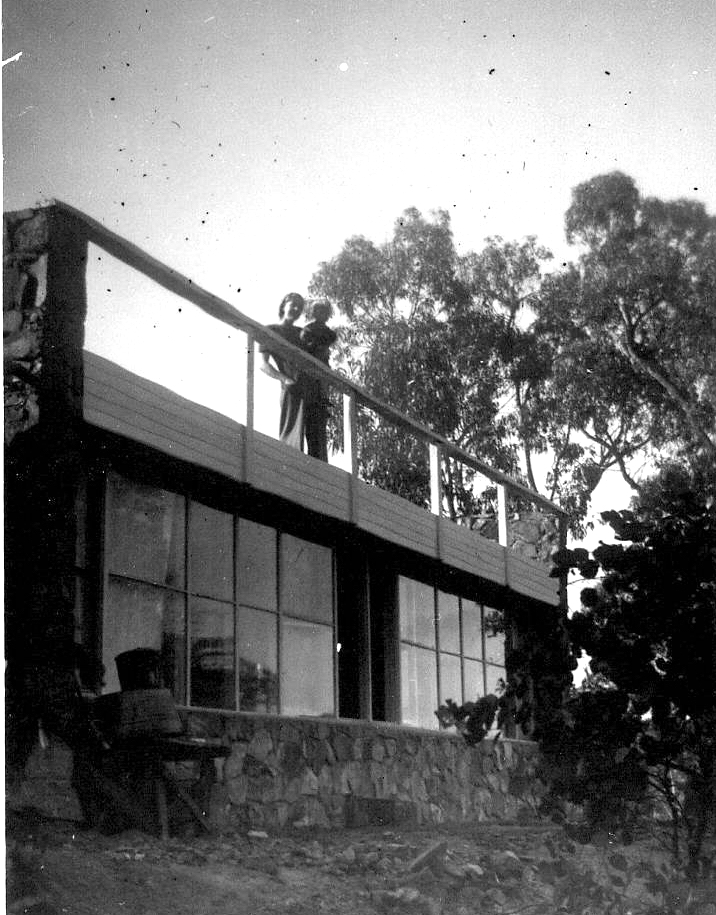

The Stone House was on the valley’s north side—an ‘avant-garde’ design that boasted Australia’s first butterfly roof and a bitumen-felt sundeck that overlooked the valley. My grandmother’s cottage was on the other side of the valley, specially designed for her and Jim’s younger brother, Bill. The design was modern, with low skillion roofs clad with oiled timber and timber-lined interiors. A stone wall and fireplace separated my uncle’s bedroom from the living room. A balcony and ramp provide access to the lower garden and the pit toilet.

Fritz and his wife, Kate, both escaped from Vienna, just before the outbreak of WW2, and settled in Warrandyte. They built their home nearby, in the same valley, with the family homes close enough to be within shouting distance of one another.

Fritz joined the Faculty of Architecture at Melbourne University in 1949, where he passed on Bauhaus design principles to a generation of Melbourne architects, including me. He made us draw what we made and make what we drew – in the Bauhaus tradition, using texture, light and shade, and form. Fritz would review our work with his quizzical eye, and talk of the future, prophesising we would all be using plastic cards as money, and that communist countries would become more capitalist and capitalist countries would become more restrictive. And I should go to America and learn about computers where they punch cards to solve problems. Advice I ignored.

The Furies

The newlyweds both experienced tragedies in their childhoods. Something they rarely talked about, and I never asked them about. I will tell you what I know. Molly was born in the year her one-year old brother died. His name was David Burden. She was 3 years old when her parents, Harold and Dorothy Burden died from tuberculosis within 2 weeks of each other. Molly’s father’s brother, Clive, fell under a train in London after returning from France, where he served as a doctor on the front-line during WW1. There were some grandparents, aunts and an uncle Frank, in Adelaide, but no one else.

Dove, Jim’s mother, became an ‘orphan’ by her grandfather’s decree. Her mother, Caroline Marion Dale, died two weeks after giving birth, without her husband, James Ernest Dale, at her side. For unknown reasons, Dove’s grandfather, who was the Archdeacon of Adelaide, prevented James from seeing his wife and newborn child.

Following Caroline’s death, the Archdeacon raised Dove, leaving James estranged from his baby daughter. James may have been traumatised by the Archdeacon’s feelings towards him after the loss of his wife. He died three years later, in May 1892, alone, in the family home in Goodwood, Adelaide. The inquest finding was quite brutal:

The body of James Ernest Dale was found dead in his bed. Verdict – Deceased came to his death by taking laudanum, administered by his own hand while under temporary insanity, brought on by his drinking habits.

The city coroner, Dr Whittell heard evidence that ‘the deceased had been in a depressed mood for some time,’ raising a mystery surrounding James (or was Ernest his preferred name?) as there was a son born to an Ernest Dale of Goodwood three months before the suicide of James Ernest Dale of Grey Street, Goodwood.1

My grandmother never mentioned a half-brother, and why would she? She was just a baby, cared for by the Archdeacon who had banished her father. A sad story and a mystery left unsolved. Jim once told me Dove loved the Archdeacon, and he adored her.

Dove was very striking in appearance—upright, aristocratic, and strong-willed. She had been “crippled” by polio since childhood and wore special high lace-up boots with raised heels, using a walking stick to manage her condition. As she grew older, she would slide on her bottom around her garden to weed and tend her flowers, continuing to enjoy life. She finally became bedridden in the mid-1970s. (I use the word “crippled” advisedly, as she displayed ferocious independence until her death at the age of 94.)

Dove had married when she was 27; her husband, Harry, was 51—an older divorced man, something frowned upon by her grandfather, Archdeacon Dove, and the rest of the Adelaide establishment.

Jim was nine years old when Harry died of prostate cancer. Harry had lain bedridden for several months, groaning in pain in the bedroom next to Jim’s, before being taken to hospital. Jim’s younger brother, Bill, was two years old.

After Harry died, the family were reliant on the good will of better off relatives. Jim recalled Dove growing and selling flowers at the local cemetery, to support the family. (Blackman).

They relied on charity from elderly aunts who would visit with a Sunday chook and provide “schooling needs” like shoes. Their better-off relatives arranged for Jim to attend Pulteney Grammar School instead of staying at the local primary school—much to Jim’s annoyance, as it meant leaving his schoolmates and the world he knew. However, as mentioned, it was there that his friendship with Berndt began, and his talent for drawing first emerged.

The Furies had done their work on the Burdens, Dales, and Doves, but a fightback was underway. Jim, raised by an ‘orphan,’ marries Molly, an orphan—what could possibly go wrong in building a future in the world the Furies had left for each of my parents?

War Time

By April 1941, Jim was in the army, working in a factory in Melbourne, making models for military war games. He said it was a bit like a regular job – you clocked in and you clock out.2 There must have been a lot of bus commuting to Warrandyte, or there wasn’t. He also had a bolt hole in the city, a place where he could draw and think.3

I’m not sure how far along the new family home had progressed by 7th December 1942, when Jim returned to Warrandyte on sick leave. I was born the following September, in Adelaide. Mum returned to the Bush Hut with me, while Jim was sent to the Sydney barracks.

I remember Mum proudly recalling how she bathed me after heating water in a cut-out 16-gallon kerosene tin over an open fire. My memory is of a dark, dank, empty interior, with the blackened tin drum lying flat on the floor. Outside, beside the entry door under an awning, on a rough timber bench, lay open plaster moulds of puppet heads and delicate papier-mâché hands.

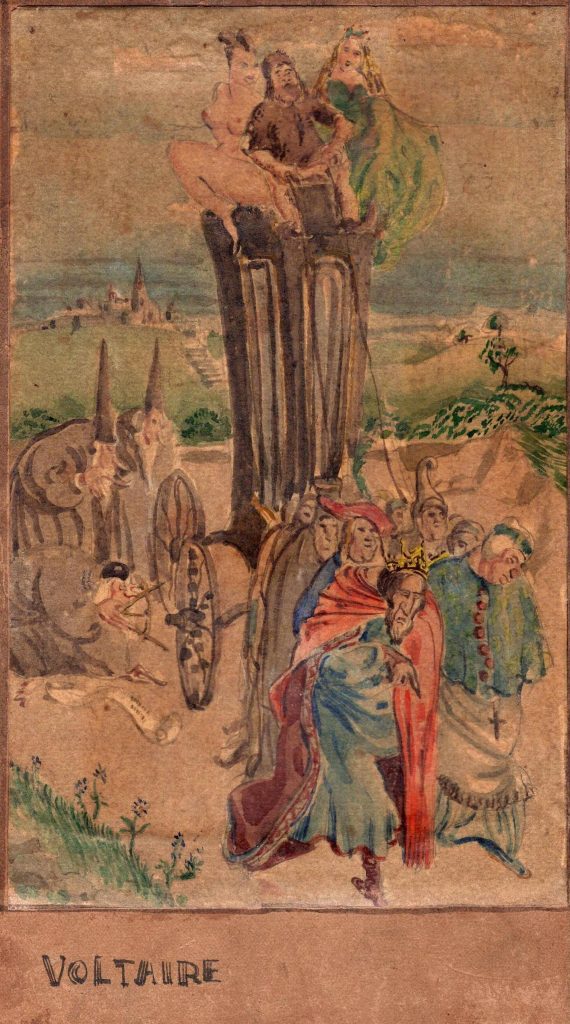

Mum may have also had time to draw and paint. However, my only memory is of a kitchen dresser decorated with a depiction of Don Quixote’s battles painted on its doors. There is also a handmade paper cover for a copy of Voltaire’s “Candide“—a guess, as the book is now lost.

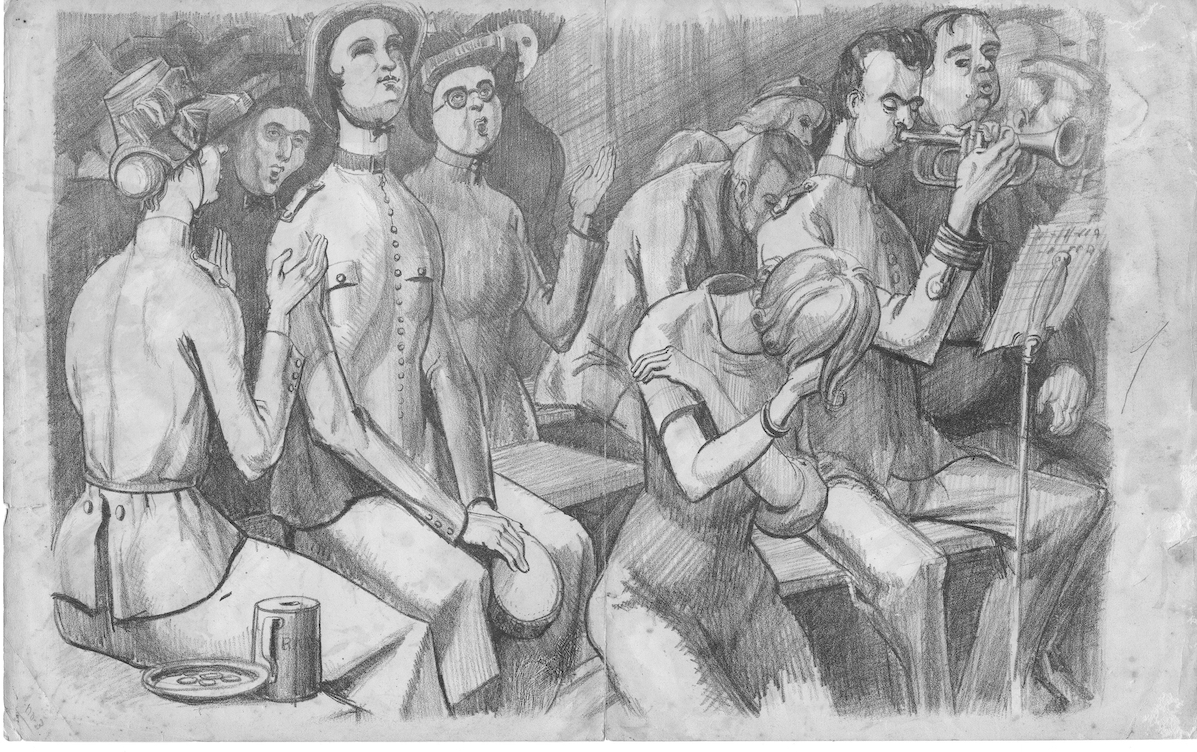

In December 1942, the gang of three (Yosl Bergner, Noel Counihan and Vic O’Connor) organised a group show to highlight the horrors of Fascism in all its forms. Jim contributed three works. For some, the exhibition was too much to stomach:

The Contemporary Art Society of Australia is holding an anti-Fascist exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery, Collins Street, to be open today at 3:30 pm. The previous antics of this society have been anti-everything, so it doesn’t really matter. On one occasion, the type of art presented by the society, caused such a revulsion of feeling in the minds and hearts of a couple of sailors that they dealt with certain records in no uncertain manner! This notice is in regard to art only, and, with a few exceptions, the work is bad– much of it hideous in colour, unreal, and shockingly drawn. I can’t understand why this bunch of people persist in creating these monstrosities. Is it an effort to gain some cheap notoriety? Some fine lithographs and etchings by Kathe Kollwitz, a German artist of great ability are included and some photographs of paintings by English war artists are to be seen. I notice bleats why are no contemporary Australian painters made official war artists?– or words to that effect. The reason I think, is obvious.

Harold B Herbert. The Argus Melbourne 8 December 1942

The exhibition included the work of Bergner, Counihan, Nolan, O’Connor, Perceval, Tucker, and James Wigley (Haese)

Herbert concluded his summary of the art on display that day by commenting on an exhibition of paintings from Koornong School in Warrandyte, referring to:

one picture by Elizabeth Lee, aged 2 years is a beauty. It completely baffled me: but it was no more baffling than a number of others I saw today elsewhere. Aged 2, mark you.

ibid

It was a time of political and intellectual battles over both the societal purpose of artists and their work and personal ambition. The internecine machinations for control and direction of the Contemporary Art Society led to the establishment of:

two radical traditions, that of the communist left, and that of the radical liberal anarchist – traditions whose values were to be a source of continuous conflict within the society…’

Haese

By 1944, the gang of three established the ‘social realists’ group, while the others clustered around Max Harris, Albert Tucker, and John Reed – The Angry Penguins. Through all this, ‘Gunner’ Wigley avoided much of the fray. He was in the army.

He was in barracks in NSW by June 1943 and went AWOL during the tail end of September, a few days after my birth. Was it a celebratory bender, or an attempt to see Mum? Another unknown. A warrant was issued for his arrest on the 5th of October, but he received remission to his sentence and rejoined his unit on the 19th of November, 1943. Four days later, he was discharged from the army—‘Not on account of Misconduct/Discreditable Service, but because he was considered unsuitable for any further military service.’4

Jim had applied for the post of Official War artist, in 1942/43 with recommendation from…. unfortunately, without success. I wonder how different his life (and ours) would have been if he had taken on that task.

After seven months of training at the Sydney barracks Jim returned to Warrandyte in December 1943, after the army had failed to teach him how to take orders from superiors.

I don’t have strong memories of Jim’s army stories about Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan, or any other artist, though they were all there. He did mention the distress army life caused Nolan– he was an ‘emotional wreck’ (or something like that, according to Jim). It doesn’t really matter as Nolan deserted it seems, in 1943, and:

…finds his artistic voice and proclaims to the world that he will be an artist, an artist who will emotionally go to war, in war paint, with art as his weapon…

Sidney Nolen Trust. See link.

I know Jim talked about the wartime Tucker, but no matter how hard I try, nothing comes to mind. I do, however, have my own memory of Tucker when he gave a lecture to architectural students at Melbourne University. It must have been part of our Fine Art subject. I don’t remember much about the lecture—maybe it was about his painting process—but I think it was more anecdotal. The only part I clearly recall is when he described drinking coffee at a Paris café and sitting in a chair where Picasso had, apparently, left a lingering fart. Tucker laughed as he told the story, though I’m not sure the audience did. Still, as you can see, the “word image” stuck with me.

On the subject of Picasso, Jim once paraphrased one of his sayings while giving me advice on painting: to always destroy the beautiful bit as you paint—if you don’t, you’ll end up painting around it. I ignored his advice and, most of the time, ended up with a lot of unfinished paintings.

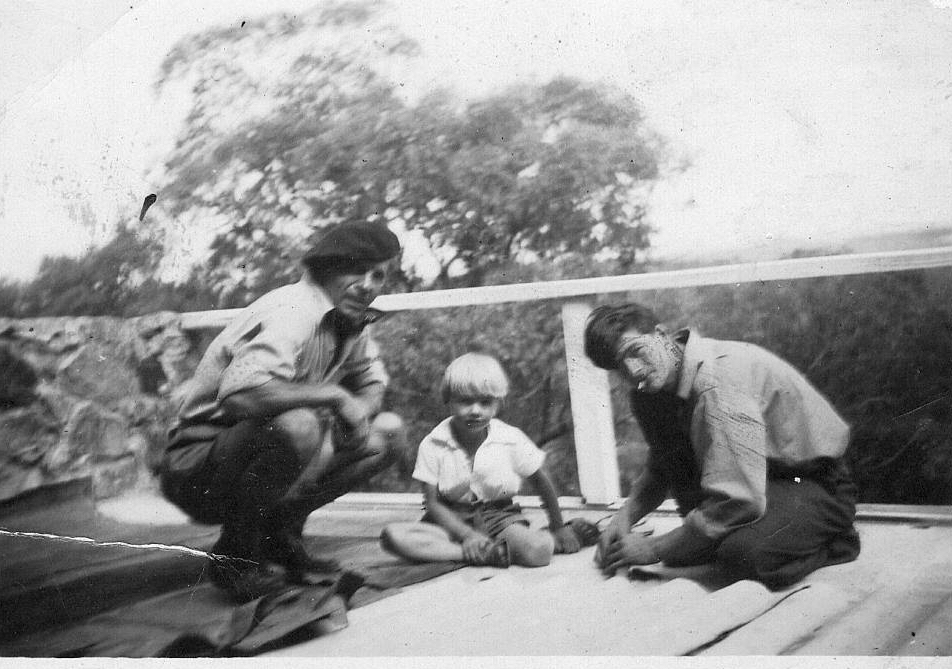

I look at photos of myself, a blond-haired, happy three-or four-year-old, clambering over stacked timber beams or playing ‘hit the nail,’ while sharp-faced men, including my father, work on the Stone House. Memories of being together with Jim and Mum from my early childhood are slight. I do recall one or two incidents, such as Jim gathering tree branches to build me a Mia-Mia in the bush behind the house. I wasn’t impressed: it was just a circle of sticks propped against a tree trunk, with no roof! It was nothing like the playhouse up the road at the Osbornes’. But from the photos, I can see a world was happening around me, and that is my story for another time.

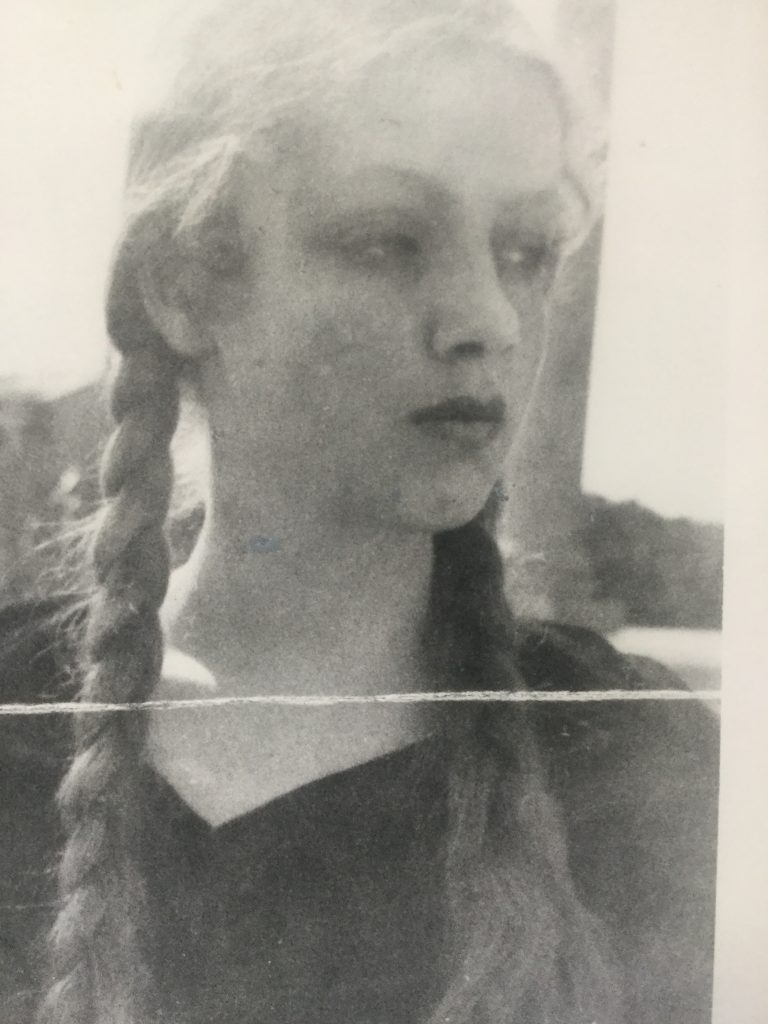

I also look at photos Albert Tucker took during his visit to the Stone House in the 1940s—photos of my mum, shy, innocent, and charming, and of my father, blurred as he carried a timber beam over his shoulder.5

Jim when interviewed by Rita Erlich in 1981, said he remembered Tucker as ‘A very angry man at that time,’ and Warrandyte as ‘A little oasis of sanity.’6

Daly River–Northern Territory

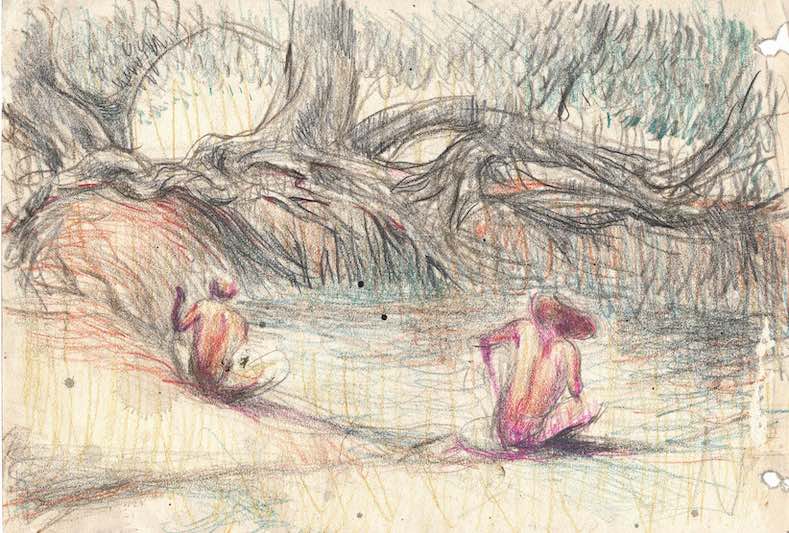

In 1945, two years after I was born, Jim travelled to the Northern Territory to join Ron and Catherine Berndt for several months on the banks of the Daly River. Jim was there to catch up with his closest friend, to draw and observe:

Wigley’s task was to record and collect examples of “native art, such as drawings, basketwork, and other handicraft (of course will go to the Department of Anthropology together with series of his own drawings). Also, he is to act as an observer, so that later his work should form the basis for our own.”

Geoffrey Gray.”He has not followed the usual sequence”: Ronald M. Berndt’s Secrets PP9-10

Jim wrote to Dove describing his life in the ‘jungle’ with the ‘natives’:

…There has already been a lot of rain, and as the ground is perfectly flat, and when dry, a blackish dust, it does not take much to turn it into a swamp, also there are frequent dry creeks, and patches of jungle. The road just runs into the creeks, no bridges … and the jungle is just a mass of tangled trees bamboo and creeper roots and the road a kind of tunnel thru it, around the river here the undergrowth and trees are luxuriant the jungle along the banks is so thick that no sun penetrates and one can walk for miles through giant corridors on a carpet of rotted leaves the trees are tremendous and architectural, the great roots sweep up curves of 20 feet or so before the massive trunk and branches even begin.

We are camped about 100 yards back from the river amongst the forest of white swamp gums and native plums (a teeny purplish tart berry, with rather nice flavour), but makes your mouth rather sore…

Letter to his Mother. Wednesday 5 Dec 1945 sent from Daly River, NT.

It would seem Jim preferred the whine of mosquitoes on the banks of the Daly River rather the demands of his two-year old son. But an artist has to do what an artist must. Floodwaters extended his stay beyond the expected few weeks. He recounts standing ankle deep in water shared with snakes, centipedes and scorpions.

Jim’s experience with the Berndts tempted him to join the anthropologist A.P. Elkin, who was in Groote Eylandt when invited. However, he soon remembered he had a wife and family to return to. “I was not a responsible person,” he recounted to Barbara Blackman in 1987.

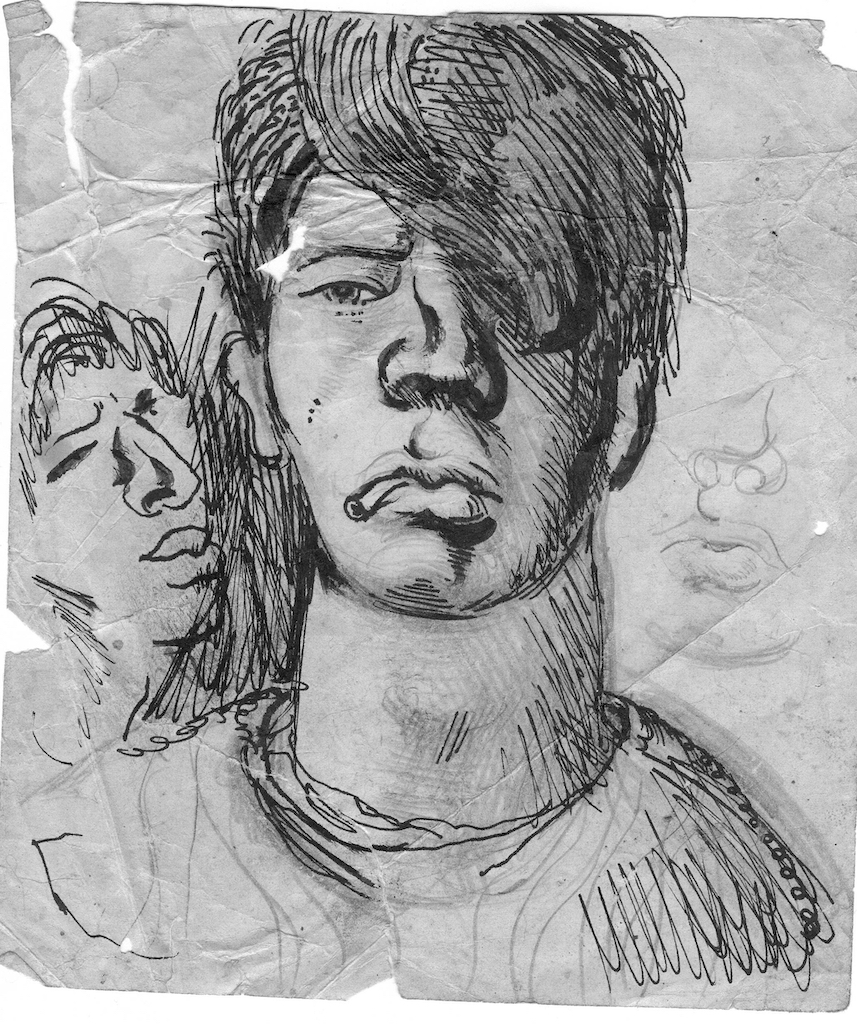

The word pictures unfolding in his letters to his mother would become recurring themes throughout his artistic career. He rendered scenes with unique drawing sensibility and humanist eye, depicting blackfellas in their country. Jim explained to Blackman that it takes a long time to truly see Aboriginal people—they could be visible one moment and vanish the next. The camera, he noted, could never truly capture the relationship between the people and their land.

The natives here are a coastal and trading people, (we are only about 60 miles from the coast here) with strong intermixtures of Malaysian, Chinese and Indonesian blood. They are very economically minded and think always in terms of trade. Many of them have wonderful and[sic] heads, so full of serenity and power that white faces indeed do seem insipid as Ron said. But they are only dirty niggers and must be kicked and cursed less they get cheeky. treacherous and hangdog rats, and indeed so the poor devils look sometimes, before the big white boss, bedecked in their bedraggled giggle suits and old army hats.

One middle aged man I sketched in the camp, fat and obese he looked, in a filthy old suit and felt hat. But later in the day I met him in the jungle, striding along stark naked with his spears and five piccaninnies, very stern, tall and dignified, going off fishing.

Today, I sat in Nim’s shade. Nim was a hunter of alligators, until he was injured by a car, and now his hand and foot are terribly maimed. He was looking at one of those American magazines full of advertisements for food. “Tucker,” he said, hmm not tucker, behind him his wife squatted before a pile of leaves on which lay two pieces of Wallaby meat, that she was singeing by waving a burning stick over which she at the same time fanned with a wild turkey wing to keep burning.

Letter to his Mother Wednesday, 5 Dec 1945 sent from Daly River, NT.

Jim’s luggage with all his drawing materials, that included 5 quids worth of paper, some of his best brushes and his tube colours was lost in transit, and he had to resort to sketching with soft lumber crayons on brown wrapping paper. He complained to his mother the crayons did not allow him much scope.

Jim and the Berndts lived off bananas, pawpaw, mangos and peanuts when in season, as well as plenty of fish and turtle and the occasional wallaby tail:

… we do not live badly, and pay only a little tea, sugar and flour or tobacco for the food. Money is valueless up here, to natives…

Ibid

When I asked Jim about his time with the Berndt’s in at Daly River, he said, ‘Catherine was ‘not pleased to see me turn up. She told me to set up camp some distance away from theirs.’– a reasonable request. ‘She didn’t like me much,’ he added. Catherine saw Jim as Ron’s “artist friend” (Gray).

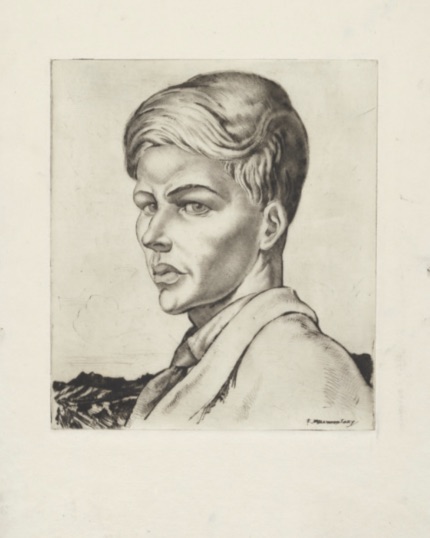

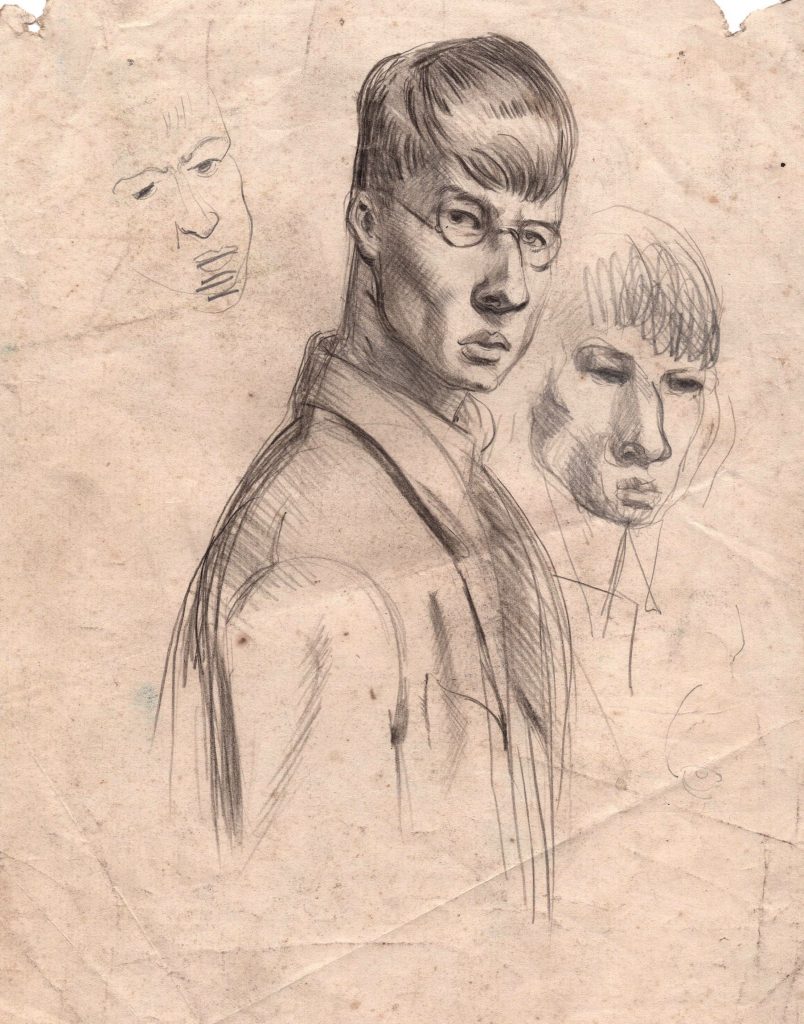

I don’t remember what Jim said about Ron when we talked about his time with the Berndts. The one drawing I have, of a youthful Ron, shows respect in its point of view – the intensity of expression and defiant posture. Ron saw the younger Jim as:

“rather unassuming and possessed of not too much money. He is a trained artist…. He has done a little work among ‘half castes’ both in S[outh] A[ustralia] and in Victoria.” Berndt also extolled Wigley’s practical skills. He had built his own house, ‘‘‘to make ends meet.’’’

Gray

Jim returned home after his stay at the Berndts’ camp with drawings and ideas for larger works. Noel Counihan referred to Jim’s portfolio of hundreds of drawings as…

Often bitter in their realism, these works present a unique picture of the tragic aboriginal (sic) people, whose culture and very existence we are ruthlessly destroying.

The Australian Artist ‘The social aspects of Australian Drawing’ By Noel Counihan. Page 22 Published Victorian Artists Society 1947

Jim attended the National Gallery art school and went on to paint his experiences rather to the annoyance of the Bulletin Art Critic:

The Aboriginal drawings and paintings of James Wigley, at the Velasquez Gallery, Melbourne, were done during a stay of nine months in native camps on the Daly and the Adelaide rivers in the N.T. They are a good illustration of the fact that art has nothing to do with propaganda. In his dark and roughly painted oils of drunken half-castes, white bosses and native hirelings, tobacco handouts and other familiar scenes of the outback, Wigley has endeavoured to arouse the sympathy of the white Australian for the degradation, misery and mismanagement of original owners of the country. All he arouses is irritation at his own inability to establish the simplest relations of colour, tone and form in his pictures. Nobody feels that about Rembrandt’s paintings of similarly persecuted Jews and beggars.

Bulletin May 14 1947. Reviewed Briefly- Artbursts. Critic not named. [Exhibition at Tye’s Building].

Mr Wigley’s drawings, where he hasn’t tried to be a propagandist, are better, though some of them intrude into the domain of caricature. “Argument”, a sincere sketch of an abo. virago in a nightdress pouring out vituperation on the landscape, is one of the best of them.

However, not everyone thought this, as the National Gallery of Victoria purchased one of the dark and roughly painted oils.

If Jim felt unconfident as a painter when he joined the Melbourne scene, Noel’s comments, put in print, would not have helped:

… James Wigley is a natural draughtsman, whose work will undoubtedly attract a great deal of attention. A less experienced painter, than either Bergner, or O’Connor, he has reached the highest development of his talent in his drawing. He has a marked feeling for line, sharp powers of observation, and an ability to grasp rapidly complex forms, to relate the lesser parts to the whole, and a firm confident hand…

Ibid

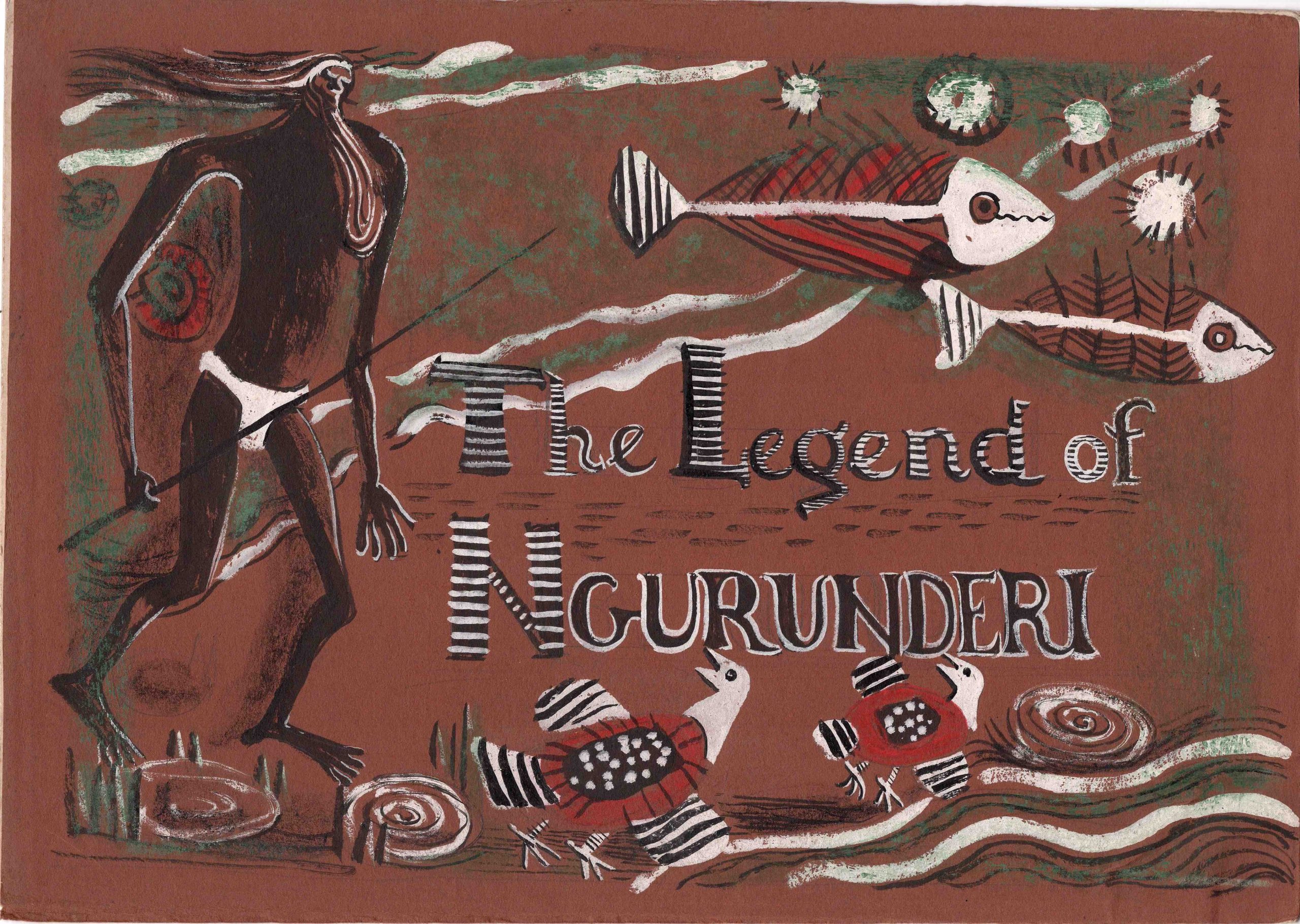

Jim Wigley’s Dividing the fishes c.1947 came from his first one-man exhibition. Held at Tye’s Gallery, Melbourne, it comprised paintings of Aborigines completed during a six-month visit to the Daley River area of the Northern Territory. The artist was surprised by the Gallery’s purchase of the work, which has rarely, if ever, been displayed.

The Violent vision of the 1940’s Jan Minchin 2014 26 June.)

In the living room of the Stone House hung Jim’s The Turtle, a companion to Dividing the Fishes, completed after his 1945 trip to the Daly River. I would lose myself in this large dark painting of a blackfella family – men, woman and children – clustered inside an open-faced, platformed, bark-clad humpy, with a small fire smouldering at the entrance and a tortoise attempting to escape a man’s waiting upturned hand.

I once pondered the possible life my father could have explored if booze had not got in his way. He had every opportunity: a favourite son of Adelaide with promise and support in the art world, friendships that provided intellectual stimulation, and a supportive family. But those around him chose differently. Take his friendship with Ron:

… Ronald, maintained his friendship until the late 1950s when “Wigley’s drinking became a problem for Catherine, who as a result asked Ronald to distance himself from Wigley.” It is about this period that the friendship deteriorates,” his colleague John Wilson remembered…

Ibid

I can blame his war years and the boredom he endured with the endless drills and taking orders in the regimented parade grounds of the Sydney and Melbourne barracks. But that’s too easy: there were fascists to fight and overcome, and he was doing his duty, one of many. Like so many others, after the war ended, he had to face his own demons and make choices. So I will tell his story as I know it, remembering Jim’s life was what it was. I’ve learned that pondering ‘what should have been’ is a waste of breath.

Artists, School and Communists in the Hills of Warrandyte

When my father was real, he lived up the hill, in the Stone House with mum and me.

I got a glimpse into my parent’s earlier life together when I met Leonard French in 1964. He was judging a mural for display in the Student Union Cafeteria at Melbourne University and had selected my expressionist cartoon and another student’s abstract painting to hang in the union cafeteria.7 Over coffee, he told me of his visits to the “Warrandyte stone house up the hill,” to party, where he met other painters and writers. Leonard must have been in his late teens or early 20s. I remember a complicated copper still, with tubes and bottles in the downstairs laundry and the bathtub full of beer bottles. I have no memories of ‘wild parties.’

Both Jim and Mum worked at the Koornong School—Mum only occasionally, helping out. On her way, she would drop me off at Stonygrad, Danila’s ever-growing stone and log studio and home, where he put me to work grinding stones. I remember the noise, water, and dust, longing for it all to end.

I remember him as a grumpy man with a finicky eye for smooth surfaces. Whenever I offered my finished lump of mudstone, which I thought was finished, he would say, ‘More grinding.’ But Vassilieff solved my problem of having the same first name as my father by calling me ‘Jay,’ named after the chattering ‘BlueJay’– raising the possibility that he was grumpy because I was annoying.

When I was five or six, I would look at a black and white photo left behind by Jim of a bare-chested blackfella, with a big belly and a smiling face, and wondered who he was and why he hadn’t visited Jim at Warrandyte. He was from the place where Jim would go. Several decades later, I saw a coloured pencil drawing by Jim titled “Karloan’s Hut Murray Bridge” (1940). In it stood a suited Aboriginal man, complete with waistcoat—the same smiling man—talking with Ronald Berndt and Albert Karloan. My childhood mystery man finally had a name and a place: Mark Wilson from South Australia.

The construction of the Stone House was a slow process—a mix of builder and friends—and by August 1945, it was only partially finished. Mum recalled her argument with Fritz over her preference for a roof that didn’t leak rather than pay for the most recent lever action copper toilet pan sluicing to a septic tank. I remember using the toilet pan, and the roof leaked, and I received my first architectural lesson without realising it.

My childhood playground was the Warrandyte bush, beside the banks of Yarra river, with its rapids, deep pools, sandy shallows and banks of coloured clays, where I watched whirlpools form in the eddies of the river’s current, fearful but fascinated, as leaves and sticks disappeared beneath the spiralling water. Most summer weekends, the cheerful Mrs Buzacott set up her picnic rug under her umbrella, on the sandy edge of the river away from the riffle beneath the Warrandyte bridge, and kept an eye on us local kids swim and play. I don’t know if Mrs Buzacott was Nutter Buzacott’s wife, Winifred, or his mother, but I do know she provided much-coveted Kraft cheese sandwiches in between the life and death battles between floating ‘belly tanks’ from B52 bombers, and inflated tractor inner tubes, with an occasional upturned ‘submarine’ canoe. A sinking belly tank was no fun in the heat of battle, particularly if roped to your ankle for easy retrieval… something you only did once.

I thought of Mrs Buzacott as a kind stranger, who offered me sandwiches because I was alone, at the water’s edge, unaware her care was likely a favour to Mum, as they knew each other. Jim spoke kindly of Nutter Buzacott, a fellow artist, and mentioned that he helped in the construction of the Stone House. In 1942 they exhibited together, alongside Yosl (Bergner) and Noel (Counihan), at the Kadimah Cultural Centre in Carlton.

The Gang of Three…and Jim

After his discharge from the Army, Jim must have been busy finishing the house with a local builder because, by 1946, he attended the National Gallery School under the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Training Scheme, where he joined Yosl and other artists. Yosl had also previously enlisted but was delegated to an army labour company unloading trains at the Victorian and New South Wales border, and after his discharge from the Army, he attended the Gallery School. 7 A time that changed all our lives.

Jim befriended his fellow students and became part of the social realist group of artists:

The Melbourne realist were primarily a group of friends, mainly ex-servicemen, who studied at the National Gallery Art School immediately after the war; the number originally included Yosl Bergner, James, Wigley, Peter Miller, Victor O’Connor, Sam Fullbrook, Jack Freeman and David Armfield. Although not National Gallery students at the time, Counihan, George Luke, and Ailsa Donaldson (who afterwards became O’Connor’s wife) also belonged to the group, and Bernard Rust later became a prominent member.

Noel Counihan by Max Dimmack. 1974. p32

Yosl and the head of the Gallery School, William Dargie, clashed over what was art – and Expressionism wasn’t art. Jim also clashed with Dargie:

On his return to Melbourne [from Daly River], Wigley entered the National Gallery Art School. The head was academic artist, William Dargie who feared the influence of the radical Wigley on younger, more conforming students. Dargie tried to sack Wigley on the grounds that he had been a practising artist before the war; but Wigley was more than a match for the principal and remained to finish his course.

Painter found inspiration among the oppressed. Jim’s obituary by Philip Jones .1999

Negotiations led to Jim and Yosl working down in the school’s basement. Jim in one corner, working on his Daly River paintings, and Yosl in the other corner, working on his Ghetto series. 7

Jim was at the gallery to learn how to paint, as he felt intimidated by other artists who used oil paint. Jim believed he was untutored in using paint as his earlier mentor, Millward Grey, saw drawing as a priority over painting. This may have led Jim and Yosl to use a bitumen additive in their oil paintings at the gallery school, or perhaps it was simply due to a lack of funds. Whatever the reason, some additives have darkened the paintings over time. I remember Jim grumbling about using bitumen as we looked at the dark surface of his 1946 oil painting, Waiting.

I rarely opened Jim’s copy of Max Doerner’s The Materials of the Artist since he gave it to me. Written in 1935, its esoteric take on the chemistry of materials and mediums felt outdated for a ‘modern,’ untrained painter in a hurry—my loss. The 400-page book, with its well-worn cover and unmarked pages, has a note on Page 88 warning against using bitumen in every technique, including fresco. However, Doerner added that the old masters, Rembrandt, for one, used it as a glaze, and as such, it did no damage.

Other painters followed the two troublemakers—Yosl with his ‘degenerate’ expressionism and Jim with his politics—to the basement. Sam Fullbrook may have been one of those students, but it would be a curious move, as Dargie considered Sam a favourite and described him ‘…as one of the best natural talents I have ever met and the only one who really understood…’ 8

My uncle, a friend of Sam’s, took me to visit Sam’s rusty houseboat moored on the Maribyrnong River when I was a kid. I liked the idea of living on a boat and thought That’s the life.

I met Sam again years later when he was staying at the Windsor Hotel in Melbourne. His rough and easy yet occasionally blunt attitude stood in stark contrast to the hotel’s refined surroundings. Things were going well for him. His crusty persona also stood in stark contrast to his delicate use of colour and transparency in his painting.

I’m not sure of Jim’s relationship with Sam, as many years later, I witnessed an expletive departure from the Milton Street flat when they were both in their seventies. I missed the gist of their disagreement, and at the time, Sam suggested I visit him as he left to return to his horses and antique furniture waiting at his country home. When I finally got around to it, he was dead. 9

As can happen, we ended up living nearby when Sam was no longer, but his memory lingered on with the local life drawing group I had joined. ‘He would make a few lines’—sensuous lines I am sure— ‘then toss the drawing on the floor, and say, “That should bring a few thousand,” and then retire for a snooze on a nearby couch.’

The Brothers

If Jim wasn’t in the basement of the Gallery School or in the Stone House with Mum and me, he was somewhere else — the disappearing man. One such ‘somewhere’ was the Omonia, a Melbourne Greek café where he occasionally met his brother, Bill. And on one such occasion, detained by the police for unruly behaviour. During the scuffle, Jim called the police ‘scabs‘ and, for his defence, declared he was following a ‘principle of the Communist system to upset law and order.’ Bill told the magistrate he was the only one telling the truth – ‘all the witnesses, including his brother, had lied in evidence.’ 7 I asked Bill why he dobbed in his brother: ‘If he had gone on any longer, we would have both ended up in jail.’ Ian Turner, the student activist and later historian, witnessed the incident:

I was eating with Alan Durre, a good non-party friend and a promising scientist who died unhappily young, at the Omonia, a Greek café much favoured by students for its large serves at reasonable prices of spaghetti and pastitsia and lamb-with-almost-anything. The two men at the next table, were happily drunk and reading a copy of the Guardian which they had bought from Charlie O’Shaunessy, who wore an eye-shade and sandshoes with a leather cash bag and spent most of his nights selling party literature around the Chinese and Greek cafes in Lonsdale, Russell and Little Bourke streets. Three plain clothes cops came into the café and began to question our neighbours. After a heated exchange, they ordered them outside. There wasn’t anything that Alan and I could do about it except smoulder, so we finished our meal. A week or so later, in the back bar of the Swanson Family – into which the entire Melbourne left-wing intelligentsia, together with interstate visitors and ASIO agents, regularly crowded – Brian Fitzpatrick describe the arrest of two men on charges of assaulting the police, and how the police had in fact assaulted them. The men were our neighbours in the Omonia. They were the painter, Jim Wigley and his civil servant brother, Bill, and they were suing the police for assault. Alan and I volunteered our evidence. The first question that Ray Dunn (for the police) asked me in cross-examination was: “Are you a Communist?” I agreed that I was. We had a brief exchange about communism and anarchism and attitudes towards the police, which I thought I won. But the Wigley’s lost their case against the police and Bill lost his job …

Page 33. Ian Turner-My Long March. Overland (Spring) 1974

Amirah Inglis, married to Ian Turner at the time, recounted his appearance in court as a witness for Jim and Bill:

[Ian] still smarted from his cross-examination by Ray Dunn, the ruthless police barrister, when as a student he had been called as defence witness to police violence against painter Jim Wigley. Civil liberties had taken up the case, and as Ian had been eating at the Greeks that night and seen the incident, he took the stand confidently. Dunn disposed of his truthful evidence by asking first if Ian were a Communist, and then quoting Communist text to show that Communists would lie for the cause; he destroyed Ian’s credibility and reduced him to shaking impotence.

Pages 67-68 Amirah Inglis. The Hammer & Sickle and the washing up. Hyland House 1995

The magistrate came down on the side of the police, fining Jim 2 pounds or 7 days jail for assault, and a further 5 pounds or 14 days jail for ‘insulting words’ – scab and a revolting insect – and Bill was fined 1 pound or 3 days in jail for assault. The brothers had to pay costs. The incident was a hiccup for Jim and Bill, as the ‘conviction’ could be boasted as a badge of honour. It was more than a hiccup for Ian:

… his appearance in court brought further trouble. He retained the position as the SRC [Student Representative Council] president, after the left rallied behind him to defeat a motion of ‘no confidence’ moved against him, and the Party reprimanded him for disclosing his membership to the public.

Ibid

This was in 1947—the Cold War was looming.

The End of a Dream

The bohemian life of politics and art in country towns gives rise to gossip and innuendo, no matter what era: Mum said she heard mothers whisper, “She’s a communist, you know,’ when dropping me off at the Warrandyte crèche. My uncle, a teenager then, said, “No such thing could happen in progressive Warrandyte.” What would he know! And anyway, Mum wasn’t a card-carrying communist. Bill said the Communist Party wouldn’t have him: “They didn’t want the Wigleys.” He likely followed up with a quote from the other Marx: “I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member.”

There is no doubt Jim enjoyed disrupting the petite bourgeoises. A problematic path for an artist to walk and talk in the viewing rooms of art galleries when asked to sip champagne with monied patrons and make small talk.

Over the years, when drunk, he would rant and yell accusations of bourgeoise thinking from darkened side streets outside our home – or wherever he found us. These were his wandering years, his life disrupted by military service – men and drinking – and meeting men and women who escaped before the ravages of war, who talked of new ideas, painted in new ways, and danced in new ways.

The war in Europe ended in May 1945, and Menzies was beating his anti-communist drum of “Reds under Beds,” preparing for the 1951 referendum to ban the Communist Party. Paranoia was high—I remember hearing of ASIO agents prowling Collins Street with concealed oil cans, squirting the backs of suspected communists with oil slicks… or was this my imagination? I would think of this when I jiggled my way down Collins Street after visiting the dentist with Mum, singing silently to myself: “Step on a crack, break your grandmother’s back.”

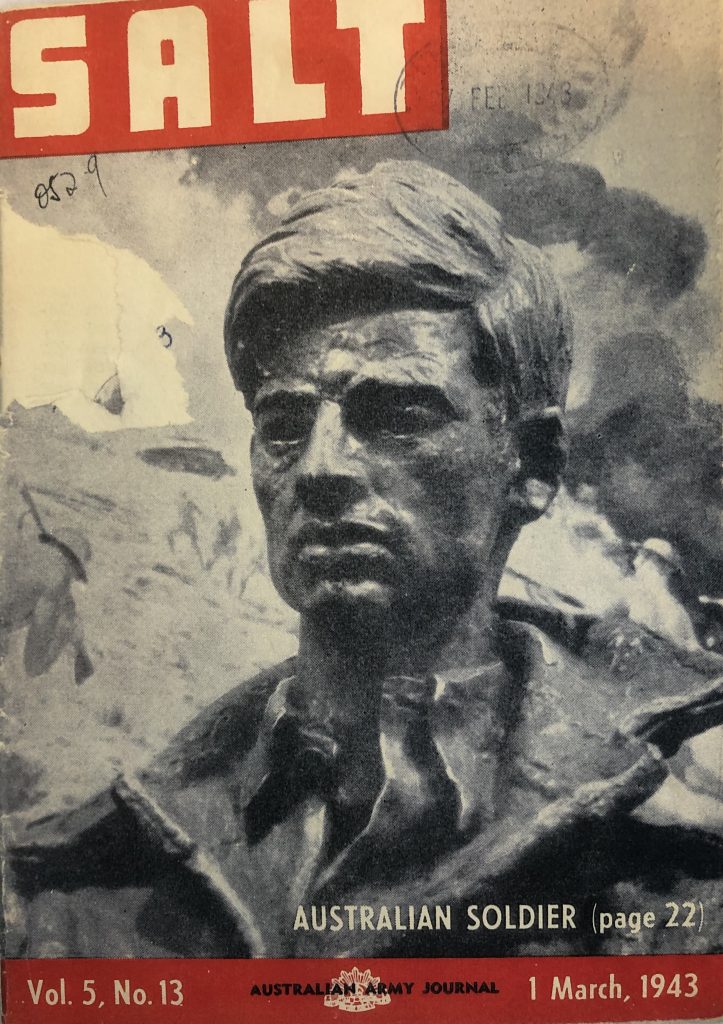

There were many gaps in my life with Jim over the years, coming together more often as we both got older. In my early teens, I treasured a battered suitcase I found under my grandmother’s house that contained some things of his: a painting in the style of Picasso meets Giorgio de Chirico, held in a broken frame; a few copies of Lilliput magazine, filled with cartoons and coloured drawings of scantily clad, long-legged ladies posing on stools or lounging on cushioned couches; some pencil and charcoal drawings; and copies of the Army magazine, SALT.

The cover of a 1943 edition was special and surprising – as it boasted a photo of Jim’s bust, called ‘Gunner Wigley‘ by the sculptor Ray Ewers. He looked stoic and brave, without his helmet, surrounded by explosions and trench-climbing soldiers: a ghost. I saw a bronze version, made in 2000, on permanent display at the War Memorial in Canberra, celebrating navy and army servicemen – until it wasn’t, due to renovations. Jim recounted:

It was nicer in the army actually, than on leave. One thing about being in the army, you hear nothing about war at all, it’s all about drill and having your gaiters done up.7

I stayed with Dove quite a bit as a kid, sleeping on her couch in the living room or Bill’s room after he moved to live under the house. I assume it was for privacy in his makeshift bedroom. I remember watching him come home from work, dressed in a waistcoated suit, carrying his briefcase, before disappearing under the house. He’d occasionally reemerge for dinner—often tripe in white sauce—prepared by his mother.

When Bill wasn’t demonstrating ‘Chinese burns’ on my arm or teasing me about my lack of reading skills, he worked at the Personal Practice Branch of the Industrial Welfare Division of the Department of Labour and National Service. His job was in a ‘special department, looking into fluorescent lighting,’ a relatively new innovation at the time, gaining attention worldwide. The Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, set up the department to handle post-war changes and avoid industrial unrest:

The department’s functions were general labour policy, manpower priorities, investigations of labour supply and labour demand, the effective placement of labour, technical training, industrial relations and industrial welfare, and planning for post-war rehabilitation and development.

Wikipedia

Bill continued the Wigley family tradition in the law, specialising in workers’ compensation and industrial accidents. He claimed his ‘Omonia’ experience spurred him to leave the public service and complete his law articles. He was admitted as a barrister and solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria and the High Court of Australia on 1 May 1955. He also reckoned he would have been a good artist, even implying he was better than his brother. He never painted or drew after leaving Koonong School.

The Furies arise

In May 1947, Jim held a solo exhibition at Velasquez Galleries in Melbourne, showing his drawings and paintings based on his Daly River experiences. 8 The show’s success provided him with some money and, apparently, an opportunity to consider his options. By this time, he likely began an affair with Ruth, Yosl Bergner’s sister, whose married name was Blima Pilley. In 1947, Ruth was busy travelling and performing alongside the Indian dancer Shivaram in cities such as Melbourne, Adelaide, and Sydney.

For Jim, there were oceans to cross and fame to be sought before any thought of returning to paint and draw the people and landscapes of northern Australia.

Jim and Yosl headed for post-war Paris in late January 1948 to establish themselves in the broader art world. Jim left Mum to finalise the building of Dove’s cottage, and when finished, she was to join him in London. Ruth had sailed earlier, after performing with Shivaram in Fiji, arriving in London in December, 1947, on her way to Paris.

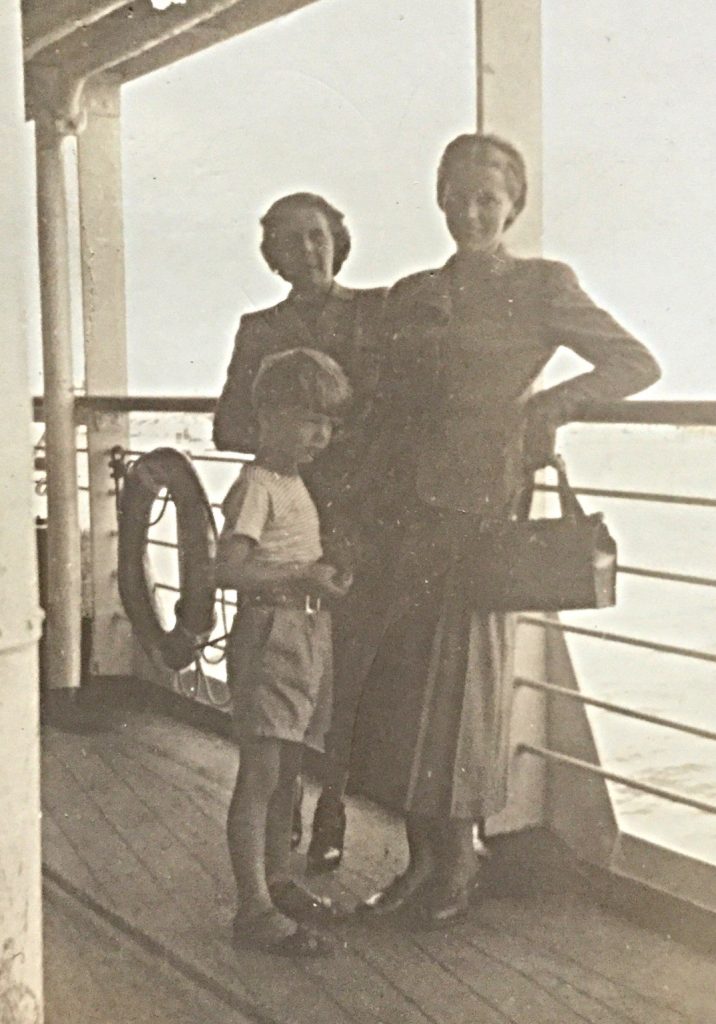

A year later, Mum rented out the Stone House and, with me in tow, boarded the Oransay, Strathaird line and travelled to London to meet up with Jim to reunite for a holiday before returning to Australia later in the year. For some reason, our departure scored a mention in the ‘Life of Melbourne’ pages of the Argus Newspaper:

Passenger in the Strathaird next week will be Mrs Jim Wigley, who will be met in England by her artist husband. Their five-year-old son, Julian, will travel with his mother.

Jim has been in Paris for some time studying and visiting galleries, and has held an exhibition there. Trio intend to spend most of their time in that city, and will return to Australia in about six months’ time.

Many of their friends at Warrandyte have given farewell parties, among them Mrs Alec Smith, Mrs Reg Preston and Mrs Philip Winne.

The Argus 6 January,1949.

The furies may be subdued in Europe, allowing the world to rebuild, but they were stirring in the southern corner, in the Warrandyte hills. Or was it Bunjil, the great eagle, the ever-watchful creator of the world, who saw all the wrongdoing and decided to release the furies?

***

PART 2

Molly and Jim

Mum didn’t find Jim settled in London. He was in France, living in the Marais, the Jewish quarter of Paris, with Josel Bergner and his sister, Ruth, with whom Jim had grown ‘very fond‘. Our arrival required Jim to leave Hotel d’Anvers and join us in London.

He left Paris at 8:00 am on Monday, January 7, 1949, and crossed the Channel to England.

…don’t really much feel like leaving Paris, but in a way it will be a good thing to see something new again – Paris getting very cold again …

JVW to Dove Feb 3rd 1949 A04

He was amazed to arrive in London by 3:30 pm that afternoon… in my mind, London is still a thousand miles away… Meanwhile, we had left Colombo, our ship steaming towards London to meet him.

He had left a high level of anxiety at the Hotel D’Anvers: Ruth was expecting her husband to turn up at any time. Yosel was shitting himself that Audrey had found out about Marg – and he had received a snotty telegram from Marg saying she would not come to Paris. There was no ‘love’ annotation – who said words don’t matter.

I will never know if Mum already knew of Jim’s infidelity before we headed to London. When she found out by letter after we returned to Warrandyte, she was shocked and ‘turned to jelly’ – if I believe what Jim wrote to his mother. To be continued.

NOTES

PART 1

- Ernest was the third child of thirteen and the eldest male. He left the family in England to immigrate to Australia. ↩︎

- Blackman ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- AWM: Service records. ↩︎

- Albert Tucker photos of Molly and Jim Wigley ↩︎

- Wigley’s life, is there, on the wall. Interview with Rita Erlich. The Age, 22 May 1981 ↩︎

- Wigley’s life, is there, on the wall. Interview with Rita Erlich. The Age, 22 May 1981 ↩︎

References and Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the following texts for providing additional information about his time at the National Gallery School and his association with other artists:

The Blackman Tapes. National Library of Australia. (Barbara Blackman’s interviewing Jim in 1988).

The Barbara Blackman tapes are also cited as ‘Blackman’ throughout the text.

Max Dimmack. Noel Counihan 1974.

Geoffrey Gray, Cluttering up the Department, reCollectionsVol 2, No2 Paper, 2007.

Geoffrey Gray. “He has not followed the usual sequence”:

Ronald M. Berndt’s Secrets* Journal of Historical Biography 16 (Autumn 2014): 61-92, www.ufv.ca/jhb. © Journal of Historical Biography 2014.

Richard Haese, Rebels and Precursors, 1981.

Jan Helma and Richard Haese, Yosl Bergner – A Retrospective Exhibition, catalogue, 1985

Inge Kral and Darren Jorgensen — James Wigley and the Strelley Mob: Social Realist Painting in an Aboriginal Community .

Charles Merewether, Art and Social Commitment – An End to the City of Dreams, 1984.

Sheridan Palmer and Jane Eckett — James Vandeluer Wigley (1917–1999)